AIR & SPACE POWER JOURNAL FALL 2021 57

AIR & SPACE POWER JOURNAL - TECHNOLOGY

Directed-Energy Weapons

An Option for Strategic De- Escalation

Alfred CAnnin

A strategist should think in terms of paralyzing, not killing. . . . And on a still higher plane,

psychological pressure on the government of a country may suce to cancel all the resources

at its command—so that the sword drops from a paralyzed hand.

—B. H. Liddell Hart, Strategy: The Indirect Approach

E

merging technological advances have provided multiple nonlethal options

to deter, deny, and incapacitate threats posed by new adversaries and

changing strategic implications. Directed- energy- weapon (DEW) op-

tions demonstrate, via an escalation of force from nonlethal to lethal, a direct

targeting capability with a high likelihood of low collateral damage and reduced

risk of civilian casualties.

e Joint Intermediate Force Capabilities Oce, formerly the Joint Nonlethal

Weapons Directorate, is exploring the function and application of nonlethal

DEW defense technologies across the spectrum of conventional warfare and the

competition continuum. ese technologies will allow the US military to accom-

plish the mission while protecting friendly forces “without unnecessary destruc-

tion that initiates or prolongs expensive hostilities.”

1

Current binary decision-

58 AIR & SPACE POWER JOURNAL FALL 2021

Cannin

making solutions limit early nonlethal weapon- escalation possibilities across the

entire range of military options.

2

A Case for Directed- Energy Weapons

As the United States transitions from a well- developed understanding of ter-

rorism and violent extremism to focus on strategic competition, the US military

and coalition forces will encounter similar adversary tactics, techniques, and pro-

cedures. In both operational environments, proxy belligerents pursue their objec-

tives in irregular warfare battlespaces.

3

Terrorists and violent extremists conduct

embedded operations in populated areas to conceal intent, often seeking oppor-

tunities to create collateral damage (CD) and civilian casualties (CIVCAS).

4

As seen in recent operations, US forces have limited conventional weapons’

options against hostile actors comingling with noncombatants as these adversar-

ies seek to capitalize on US kinetic operations and CIVCAS reporting.

5

Violent

extremist organizations, with the presence of the world’s media, take advantage of

mistakes and collateral damage by promulgating narratives critical of US kinetic

CD and CIVCAS reporting, shaping an “us- or- them” local propaganda message

and shifting international opinion.

6

By portraying the United States as callous and indierent to the suering of

local populations, this eective guerrilla tactic creates vulnerabilities for the

United States and coalition forces. ese vulnerabilities are especially problematic

when the US military tries to balance oensive operations and self- defense with

strategy in conventional operations and across the continuum of strategic compe-

tition. Uncertainty about the true nature of civilian casualties in the battlespace

means a delay in identifying hostile acts or intent. Under the current rules of en-

gagement (ROE) in Phase III military operations and exacerbated by the inher-

ent compression of time and space, the rapid escalation of force necessitates a

preference for lethal conventional kinetic weapons.

7

Often as a result, the compre-

hensive analysis required to identify and prosecute a threat is limited.

Traditional conventional weapon escalation- of- force scenarios also limit sys-

tem 1 (fast thinking) and system 2 (slow thinking) cognitive problem analyses

used to determine hostile intent.

8

is analytic model is vital in determining hos-

tile intent and calculating associated responses across the full spectrum of military

options, from Phase 0 to Phase V and along gray- zone continuums. Moreover,

this calculus is made even more complex by the limitations on range capabilities,

complex targeting solutions, fog (actual and metaphorical), and the inescapable

friction of war.

9

Directed- energy weapons should be used in conjunction with conventional

weaponry to provide friendly forces with various escalations- of- force capabilities,

Directed Energy Weapons

AIR & SPACE POWER JOURNAL FALL 2021 59

enabling the military to apply the minimum force required for a specic threat

versus a one- size- ts- all kinetic solution.

10

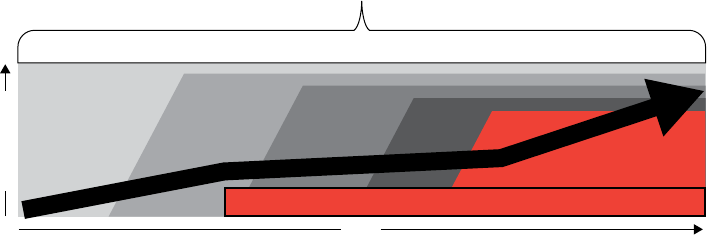

is new escalation-of-force opera-

tional concept (g. 1) complements conventional weapons with the sequential

and concurrent use of intermediate-force capabilities. Such an operational con-

cept provides the nonlethal and lethal DEW eects that Joint Force commanders

require while safeguarding US policy and strategy, limiting adversary retaliation

or escalation, and controlling battlespace information and perceptions.

e simplied targeting and speed- of- light characteristics of DEWs provide

an increased stando range for forces, allowing opportunities to prosecute hostile

threats early. With a new employment operational concept, DEW capabilities

expand the current kinetic escalation- of- force timeline, foster minimum-force

weapon applications, and increase safety for friendly forces.

Direct Energy Weapon Escalation of Force (EoF) Methodology

Time and Space Compression/Cognitive Capability/Experience/Training

NL-IFC

Deter

DEW

Disrupt

Non-Lethal HEL

Incapacitate

Lethal

HEL

Conventional

Weapons

Imminent Threat

Time

Inherent Right for Self-Defense

Threat Assessment

ROE Lethal Force Authorized

Threat to Friendly Forces

Figure 1. DEW escalation-of-force methodology

Nonlethal Directed- Energy Weapons

Bridging the gap between military presence and lethal intent, the Joint Inter-

mediate Force Capabilities Oce shapes the use of emerging nonlethal micro-

wave, millimeter, and laser- energy technologies in gray- zone operations, urban

areas, and irregular and unconventional warfare battleelds.

11

Nonlethal DEWs

are “developed and used with the intent to minimize the probability of producing

fatalities, signicant or permanent injuries, or undesired damage to material or

infrastructure.”

12

Nonlethal DEW technologies safeguard US forces against ne-

farious activities with capabilities including long- range, laser- induced plasma

audio devices that communicate US military presence, and nonlethal dispersal

and denial devices, which are silent and invisible to the human eye.

13

Additionally, silent, often nonattributable, nonlethal millimeter and microwave

devices exist to disorient personnel and disable, neutralize, and incapacitate enemy

electronic targets such as threat vehicles, vessels, and aircraft, with mitigation ben-

ets similar to those noted above for the escalation- of- force concept.

14

Nonlethal

60 AIR & SPACE POWER JOURNAL FALL 2021

Cannin

DEW options could better address a potential hostile act in uncertain bat-

tlespaces—urban—precluding an automatic, and possibly unnecessary, accelera-

tion to lethal-targeting options.

Lethal Directed- Energy Weapons

Lethal DEW, including high- energy lasers (HEL), complement nonlethal

DEW diuse capabilities in the escalation- of- force methodology, progressing

from nonlethal intermediate-force capabilities to material- kill targeting. ese

DEWs are “technologies that relate to the production of a beam of concentrated

electromagnetic energy or atomic or subatomic particles.”

15

ese technologies

are developed into weapons or systems “that use directed energy to incapacitate,

damage, or destroy enemy equipment, facilities, and/or personnel.”

16

Silent and invisible, high- energy laser systems used on countermaterial targets

can disable and destroy the mobility of positively identied personnel, minimiz-

ing conventional- weapon escalation and the secondary threat of collateral damage

and civilian casualties.

17

High- energy lasers are in the nascent stage of develop-

ment and not currently authorized. But as their power levels evolve, weapon-

quality lethal targeting options will emerge.

18

Advantages

Directed- energy weapon technologies oer a simplied aiming solution and

instantaneous targeting escalation from nonlethal intent to lethal force, resulting in

an elongated nonlethal weapons escalation- of- force window. If applied early, non-

lethal and lethal DEWs “in certain cases prevent the use of excessive force, escala-

tion in hostilities, and CD.”

19

Lethal DEW eects, highly discriminant and anti-

suering, oer a solution to minimize critical infrastructure or private property

collateral damage while still accomplishing military and political objectives. ese

weapons also remove the violent sensation and perception associated with conven-

tional kinetic weapons, avoiding third- order eects of adversary information-

operations propaganda and messaging that facilitates support and recruiting.

20

Over time, as the size, weight, power, and cooling levels of DEWs advance,

exible nonlethal and lethal DEWs are anticipated to proliferate across a diverse

range of security environments. ese capabilities could be employed more rou-

tinely than any other conventional weapon or emerging-weapons technologies.

21

The Right Tool

With various overlapping 5-Ds (deny, degrade, disrupt, deceive, or destroy)

properties, the preemptive escalation- of- force application of DEWs could resolve

Directed Energy Weapons

AIR & SPACE POWER JOURNAL FALL 2021 61

malicious activities before conventional lethal force is required. e early applica-

tion of nonlethal weapons de- escalates ambiguous situations with minimum use

of force, safeguarding friendly forces while avoiding CD and CIVCAS. ese

weapons can be applied sequentially and concurrently during the escalation of

force to demonstrate resolve while avoiding damage caused by conventional ki-

netic (blast, fragmentation, cratering, incendiary, and penetration) weapons.

During confrontations where the ROE authorize lethal force, violence is not

always immediately suitable across the range of military options, particularly in

gray- zone operations where US policy and strategy limit military operations be-

low the threshold of armed conict. e civilian population- centered approach

facilitated by nonlethal DEWs retains the hearts and minds of those the United

States defends and helps gain the long- term trust and condence of future popu-

lations facing irregular and unconventional warfare in these unstable gray- zone

battlespaces of great power competition.

22

e scalability, silent, and often nonattributable nature, damage- level selec-

tions, and immediate responsiveness (speed of light) of DEW capabilities provide

friendly forces the means to target nuisance cominglers and direct threats with a

variety of tailored, minimum- force weapons.

23

Nonlethal and lethal DEW capa-

bilities also allow for engineered warfare scenarios. e combination of eects

could greatly inuence multiple wartime missions and result in less cause for the

enemy to retaliate or escalate force. With no clear evidence of US force and at-

tribution or signature- less employment by friendly forces, the United States can

engineer the de- escalation of a potential enemy threat.

Great power competition proxies deliberately operate below the threshold of

armed conict, rendering conventional kinetic weapons incompatible as they can

“adversely aect eorts to gain or maintain legitimacy and impede the attainment

of both short- term and long- term goals.”

24

e use of intermediate-force capa-

bilities, nonlethal DEWs, and the nonlethal application of HELs are particularly

advantageous in gray- zone scenarios “when restraints on friendly weaponry, tac-

tics, and levels of violence characterize the operational environment” across the

competition continuum.

25

Although the 2017 National Security Strategy, 2018 National Defense Strategy,

and 2021 Interim National Security Strategy have refocused the Department of

Defense toward strategic competition, the nature of warfare and our adversaries’

tactics, techniques, and procedures (to operate as a wolf in sheep’s clothing, ma-

neuvering to induce CD and CIVCAS events that can then be exploited to the

disadvantage of the United States) remain unchanged.

26

Military forces operate across the spectrum of conict zones, including military

operations other than war. During such noncombat operations, the authorized

62 AIR & SPACE POWER JOURNAL FALL 2021

Cannin

use of nonlethal DEWs early in an escalation- of- force methodology increases the

envelope of time available to identify and mitigate a threat. is capability pro-

vides Joint Force commanders the technological advantage to ensure friendly-

force safety with mission success across multiple spectrums.

Alternative Consideration

Implementing DEWs, individually and as a whole, will involve the expected

hurdle of doctrine, organization, training, materiel, leadership, personnel, facili-

ties, and policy, and necessary bureaucracy. But DEWs will also face external

scrutiny. Some argue the premature, ultimately disappointing DEW technologies

in the Department of Defense are based not on results but instead on overesti-

mated technological capabilities and unrealistic timelines.

27

Others amplify this

warning, noting future budgetary constraints, challenges in adopting innovation,

and disconnects in implementation as the United States fails to capitalize on Ally

and partner relationships, particularly in DEW technologies.

28

e eects of public opinion on US decision makers are an unanticipated ob-

stacle to the implementation of existing DEWs. Highlighted by the US and inter-

national media, multiple human-rights activists and critics have raised two funda-

mental issues regarding DEW eects—safety concerns and ethics violations.

29

Culminating in 2010, controversy obscured the capabilities of the Active De-

nial System in Afghanistan.

30

Major media headlines hypersensationalized the

eects of active-denial-system weapons—in this case a microwave heat ray gun

dubbed Silent Guardian—as crippling and brutally painful, like “being exposed to

a blast furnace,” or “making people feel like they are on re.”

31

ese only partially

substantiated media spins resulted in the immediate removal of the Army active-

denial system weeks after its arrival but before its operational use—drastically

stunting the progress and momentum of DEW implementation.

32

e eectiveness of the media campaign directly conicts with the hypothesis

that nonlethal DEWs promote strategic benets and tactical prudence.

33

e ef-

fects of public opinion also highlight future requirements to purposely incorpo-

rate supportive narratives that encourage the adoption and implementation of

DEW, which include re- educating decision makers on past misunderstandings

and current capabilities.

Conclusion

New and old adversaries alike seek to exploit political perceptions regarding the

use of force. Changing US priorities have led to new challenges that modern

technologies and innovative tactics could address, providing Joint Force com-

Directed Energy Weapons

AIR & SPACE POWER JOURNAL FALL 2021 63

manders the tools to achieve military objectives and ROE authorities to execute

minimum- force eects. Directed- energy weapons, including intermediate-force,

nonlethal, and lethal capabilities, present a complementary set of useful minimum-

force options as the US military continues to operate across multiple spectrums of

conict, especially in urban environments.

Updated escalation- of- force guidance in the form of ROEs that leverage

DEW capabilities early could enable Joint Force commanders to proactively

shape battleeld conditions and avoid unnecessarily raising the level of conict.

ese weapons could mitigate second- and third- order eects of irreversible US

kinetic weapon miscalculations, thus safeguarding US strategy and political ob-

jectives, limiting adversary retaliation, and shaping battlespace information, in-

uence, and perceptions in conventional operations and across the continuum of

strategic competition.

34

Additional research should aim to quantify if eects across multiple spectrums

of conict can oset conventional weapon incompatibilities, de- escalate battle-

eld scenarios, deter adversaries, and shape battlespace information, inuence,

and perceptions. Furthermore, research must address the current escalation- of-

force model, coercion, rst- use policies, and just war theory to validate benets for

an early escalation- of- force methodology. Moreover, a clearly articulated DEW

science and technological understanding, a cost- benet analysis, and the merging

of Joint Intermediate Force Capabilities Oce intermediate- force capability doc-

trine with HELs will encourage policy makers and DOD leadership to adopt and

implement these emerging DEW capabilities.

Alfred Cannin

Major Alfred Cannin, USAF, a winged aviator in USAF Special Operations Command, holds a master of aerospace

science from Embry- Riddle Aeronautical University.

Notes

1. Wendell B. Leimbach, interview with author, September 16, 2020.

2. Sjef Orbons, “Are Non- Lethal Weapons a Viable Military Option to Strengthen the Hearts

and Minds Approach in Afghanistan?” Defense & Security Analysis 28, no. 2 (2012): 114–30.

3. Department of Defense (DOD), Summary of the Irregular Warfare Annex to the National

Defense Strategy (Washington, DC: DOD, 2020).

4. Stephen D. Davis, “Controlled Warfare: How Directed- Energy Weapons Will Enable the

US Military to Fight Eectively in an Urban Environment While Minimizing Collateral Dam-

age,” Small Wars & Insurgencies 26, no. 1 ( January 2015): 49–71.

5. Davis, “Controlled Warfare,” 49−71.

6. Orbons, “Non- Lethal Weapons,” 127.

7. Orbons, “Non‐Lethal Weapons.”

64 AIR & SPACE POWER JOURNAL FALL 2021

Cannin

8. Paul K. Van Riper, “e Identication and Education of U.S. Army Strategic inkers,” in

Exploring Strategic inking: Insights to Assess, Develop, and Retain Army Strategic inkers, ed.

Heather M. K. Wolters, Anna P. Grome, and Ryan M. Hinds (Fort Belvoir, VA: US Army Re-

search Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences, February 2013), 16–18, https://doi

.org/10.1037/e639722013-001; and Daniel Kahneman, inking, Fast and Slow (New York: Far-

rar, Straus and Giroux, 2011).

9. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Sta (CJCS), Joint Planning, Joint Publication ( JP) 5-0

(Washington, DC: CJCS, December 1, 2020), https://www.jcs.mil/; and Caleb Carr, ed., e Book

of War (New York: Modern Library, 2000).

10. CJCS, Peace Operations, JP 3-07.3, Incorporating Change 1 (Washington, DC: CJCS,

October 22, 2018), GL-4, https://www.jcs.mil/.

11. Orbons, “Non- Lethal Weapons.”

12. Ashton B. Carter, DoD Executive Agency for Non- Lethal Weapons (NLW), and NLW Policy,

DOD Directive 3000.03E, Incorporating Change 1 (Washington, DC: DOD, September 27,

2017), https://fas.org/.

13. Davis, “Controlled Warfare”; and Leimbach, interview with author.

14. Davis, “Controlled Warfare”; and Leimbach, interview with author.

15. DOD, DoD Dictionary, s.v. “directed energy,” accessed July 31, 2021, https://www.jcs.mil/.

16. DOD, DoD Dictionary, s.v. “directed energy weapon,” accessed July 31, 2021, https://www

.jcs.mil/

17. Davis, “Controlled Warfare.”

18. “Solid- State High- Energy Laser Systems,” Northrop Grumman (blog), November 9,

2020, https://www.northropgrumman.com/.

19. Davis, “Controlled Warfare,” 63.

20. Davis, “Controlled Warfare,” 49.

21. James N. Mattis, Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy of the United States of Amer-

ica: Sharpening the American Military’s Competitive Edge (Washington, DC: Oce of the Secretary

of Defense, January 2018), https://dod.defense.gov/; and Northrop Grumman, “Laser Systems.”

22. Orbons, “Non- Lethal Weapons.”

23. Joint Targeting School ( JTS), Joint Targeting School Student Guide (Dam Neck, Virginia:

JTS, March 1, 2017), https://www.jcs.mil/; Orbons, “Non‐lethal Weapons”; Davis, “Controlled

Warfare”; and Leimbach, interview with author.

24. Rudolph C. Barnes, “Military Legitimacy in OOTW: Civilians as Mission Priorities,”

Special Warfare 12, no. 4 (Fall 1999): 38–39.

25. CJCS, Joint Targeting, JP 3–60 (Washington, DC: CJCS, 2013), II–16.

26. Donald J. Trump, National Security Strategy of the United States of America (Washington,

DC: Executive Oce of the President, December 2017), https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/;

and Mattis, National Defense Strategy.

27. Ash Rossiter, “High- Energy Laser Weapons: Overpromising Readiness,” Parameters 48,

no. 4 (Winter 2018−19): 33–44, https://press.armywarcollege.edu/; and John Gourville, “Eager

Sellers and Stony Buyers Understanding the Psychology of New- Product Adoption,” Harvard

Business Review ( June 2006), https://hbr.org/.

28. Rossiter, “High- Energy Laser”; and Hugh Beard, “View from the UK: Directed Energy as

a Next Generation Capability,” (address, Booz Allen Hamilton 2019 Directed Energy Summit,

n.d.), https://www.boozallen.com/.

Directed Energy Weapons

AIR & SPACE POWER JOURNAL FALL 2021 65

29. Sharon Weinberger, “US Military Heat- Ray: Set Phasers To . . . None,” BBC News,

November 18, 2014, https://www.bbc.com/.

30. Weinberger, “Military Heat- Ray.”

31. Tim Elfrink, “Safety and Ethics Worries Sidelined a ‘Heat Ray’ for Years. e Feds Asked

about Using It on Protesters,” Washington Post, September 17, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost

.com/; and John Hudson, “Raytheon Microwave Gun Recalled Amidst Controversy,” Atlantic,

July 19, 2010, https://www.theatlantic.com/.

32. Elfrink, “Safety and Ethics”; and Noah Shachtman, “Pain Ray Recalled,” Wired, July 20,

2018, https://www.wired.com/.

33. Schachtman, “Pain Ray Recalled”; and Orbons, “Non‐Lethal Weapons.”

34. JTS, Student Guide.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed or implied in the Journal are those of the authors and should not be

construed as carrying the official sanction of the Department of Defense, Air Force, Air Education and Training

Command, Air University, or other agencies or departments of the US government. This article may be reproduced

in whole or in part without permission. If it is reproduced, the Air and Space Power Journal requests a courtesy line.