Driving crime down

Denying criminals the use of the road

October 2004

Police Standards Unit

PA: delivering value

PA Consulting Group is a leading management, systems and technology

consulting firm. Operating worldwide in more than 35 countries, PA draws

on the knowledge and experience of 3,000 people, whose skills span the

initial generation of ideas, insights and solutions all the way through to

detailed implementation.

PA focuses on creating benefits for clients rather than merely proposing them.

Our work is founded on powerful insights into our clients’ issues, and in the

private sector in particular, on the need to deliver superior shareholder returns.

We help accelerate business growth by developing innovative products for

our clients and by the application of emerging technology. We deliver major

transformation programmes, mobilize human resources, and manage complex

IT and technically-challenging programmes.

PA’s results-focused approach is founded on a unique commitment to

excellence, value and independence:

Excellence. We are committed to unremitting excellence and quality in

every aspect of our work: in our relationships with our clients, in the client

assignments we deliver, and in the people we recruit and develop, who enjoy

exciting and rewarding careers at PA.

Value. PA’s consultants bring an intense focus on delivering value through

deep industry insight, the development and application of technology, and

our culture of respect, collaboration and flexibility in working with clients.

Independence. PA is independent of outsourcing, software, hardware

and audit providers. We are the pre-eminent client-side adviser on IT and

outsourcing projects, and deliver, in partnership with our clients, business

solutions tailored to our clients’ needs, rather than solutions pre-determined

by commercial alliances. As an employee-owned company, we are answerable

to our clients and to ourselves only.

“I am pleased to be able to present this

evaluation of the pilot of automatic number

plate recognition intercept teams. I am very

grateful to the police forces that have taken part,

and thank the officers involved for their high levels

of commitment and effort that have been shown to

have delivered such impressive results.

The outcomes from the pilot are impressive:

• Between June 2003 and June 2004, ANPR

teams across 23 forces produced nine/ten times

the national average arrest rate per officer,

totalling more than 13,000 arrests

• Over the same period, officers recovered

property and drugs worth well in excess of

£8 million.

• The average ANPR-intercept officer is

responsible for 33 offences brought to justice

each year – three times the rate for other

forms of policing.

• The Home Office estimates that national roll-out

of ANPR would lead to approximately 26,400

additional offences being brought to justice each

year – a significant contribution of around 15%

towards meeting the Governement’s target for

offences brought to justice.

Although it is only one policing tool, ANPR has uses

in a range of areas, including tackling volume crime,

serious & organised crime, counterterrorism, and

in intelligence gathering. It has also proven a great

asset in tackling the ‘underclass’ of vehicles that

are incorrectly registered, untaxed and uninsured.

In recognition of this, ANPR is integral to delivering

the Home Office’s policy objectives as set out in

Confident Communities in a Secure Britain, the

Home Office strategic plan for the next five years.

It is also a crucial element of the joint Home Office,

Department for Constitutional Affairs and Crown

Prosecution Service strategy for reforming the

criminal justice system: Cutting Crime, Delivering

Justice. The experience gained in the pilot,

highlighted by the evaluation work, is likely to

lead to the introduction of ANPR enabling

legislation as soon as Parliamentary time allows.

The recent Greenaway Report on uninsured

driving also included recommendations to

maximise the effectiveness of ANPR. DfT are

currently planning measures to implement these.

The achievements and good practice established

during the pilot provide an outstanding foundation

for rolling out the concept of ANPR nationally.

This, together with further development suggested

by the evaluation, and stronger partnership

working, brings us closer to our ultimate aim

of denying criminals use of the roads.”

Home Secretary’s

Introduction

Rt Hon David Blunkett MP

Home Secretary

October 2004

2

3

This study, commissioned by the Home Office Police Standards Unit (PSU),

would not have been possible without the co-operation of the police forces

involved. We would like to thank the Chief Constables, intercept teams and

support staff of the 23 police forces that took part in this project, namely:

Avon & Somerset Constabulary Cambridgeshire Constabulary

Cheshire Constabulary City of London Police

Cleveland Police Greater Manchester Police

Hampshire Constabulary Hertfordshire Constabulary

Kent Constabulary Lancashire Constabulary

Leicestershire Constabulary Lincolnshire Police

Merseyside Police Metropolitan Police Service

North Wales Police North Yorkshire Police

Northamptonshire Police Northumbria Police

Nottinghamshire Constabulary Staffordshire Police

Warwickshire Police West Midlands Police

West Yorkshire Police

Specific thanks goes to Chief Constable Richard Brunstrom (Head of

Road Policing, ACPO), and Frank Whiteley (Chair, ANPR Steering Group),

Superindendents Alan Ford and Terry Kellaher (formerly of the Home Office

Police Standards Unit) and Robert Ritchie (Home Office, Justice Gap Taskforce).

The views expressed in this report are those of the authors, not

necessarily those of the Home Office Police Standards Unit or the

Association of Chief Police Officers. The consultants who worked on

this project were Charlie Henderson, Panikos Papagapiou, Adrian Gains

and Jim Knox. Any queries in relation to this report should be directed

Acknowledgements

4

ANPR is not a new technology, but it was only

recently that the full potential to tackle criminality

was beginning to be realised

In 2002, a number of police forces increased their use of Automatic Number

Plate Recognition (ANPR) systems to include dedicated intercept officers.

These officers were able to intercept and stop vehicles of interest identified by

the ANPR systems and question the driver and/or passengers as appropriate.

The intention was that targeted enforcement would detect, disrupt and deter

criminality. A six-month evaluation of the use of these dedicated intercept

officers (‘Laser 1’) showed the concept to be extremely effective, achieving

arrest rates many times that of conventional policing.

Although these results were encouraging, there was no funding set aside

for the national testing, roll-out and operation of ANPR-enabled intercept

teams. An innovative funding mechanism was, therefore, required. Following

a submission to HM Treasury, conditional approval was given to the Home

Office to test a cost recovery system for dedicated ANPR-enabled intercept

teams. This would allow police to target vehicle documentation offences and

crime in general with the activity part-funded through receipts from the fixed

penalties issued by these teams.

Since 1 June 2003, 23 forces across England and Wales have operated

dedicated intercept officers part-funded under cost recovery (‘Laser 2’).

Executive summary

5

This report presents the findings of the evaluation of Laser 2 for the period 1

June 2003 to 31 June 2004.

The use of ANPR intercept teams

is aligned with Government policy

The use of ANPR-enabled intercept teams to engage criminality on the road

is clearly aligned with a number of key objectives for the Police Service,

including the National Policing Plan, Strategic Plan for Criminal Justice

2004-08, the Police Service’s National Intelligence Model and the Association

of Chief Police Officers (ACPO) Road Policing strategy. The use of ANPR-

enabled intercept teams also contributes to wider objectives, specifically road

safety (eg enforcing the offences of not wearing seat belts and illegal use of

mobile telephones while driving) and excise collection (eg ensuring that all

vehicles on the road are appropriately taxed).

This also addresses the public’s desire to see more ‘officers on the street’

and more action taken against illegal drivers. Given the link between vehicle

documentation offences (which can be relatively easily identified from national

databases) and wider criminality, it can be shown that the targeting of these

offences through the use of ANPR-enabled intercept teams can make a

significant contribution to wider policy objectives.

During Laser 2, ANPR has been evaluated

in 23 forces for over a year

During the course of Laser 2 project, the total staff input across 23 forces was

368,446 hours – this equates to 192 Full Time Equivalents (FTEs), the majority

of whom were police constables. By the start of the second year of Laser 2

there were approximately 515 officers involved in ANPR related operations.

The majority of ANPR officers’ time (77%) was spent either on intercept duties

or travelling to and from intercept duties. This level of visibility is significantly

higher than a ‘typical’ police officer – a Home Office report identified that on

average a typical police officer spent only 57% of their time away from their

police station. Further, ANPR intercept officers, whether they are travelling

to and from intercept sites or undertaking intercepts can also respond to

incidents as necessary when they occur.

A key aspect to the successful exploitation of ANPR intercept teams was

senior officer commitment to the programme – this ensured that resources

were available as and when required and other officers across the force

provided appropriate intelligence for the ANPR teams to operate on.

6

The results from Laser 2 have been impressive

The ANPR intercept teams stopped a total of 180,543 vehicles.

From these stops, the intercept officers:

• arrested 13,499 persons, including:

– 2,263 arrests for theft and burglary

– 3,324 arrests for driving offences (for example driving whilst disqualified)

– 1,107 arrests for drugs offences

– 1,386 arrests for auto crime (theft from and of vehicles)

• recovered or seized property, including:

– 1,152 stolen vehicles (valued at over £7.5 million)

– 266 offensive weapons and 13 firearms

– drugs worth over £380,000 from 740 vehicles

– stolen goods worth over £640,000 from 430 vehicles

• issued fixed penalty notices, including:

– 22,825 tickets for failing to display Vehicle Excise Duty (VED)

– 6,299 for no insurance

– 1,496 for no MOT

– 20,290 for a variety of offences, including not wearing a seat belt,

using a mobile telephone whilst driving.

The evaluation also confirmed previous research that had found a correlation

between vehicle documentation offences and volume crime – 3,530 of all

arrests (26%) originated from vehicle stops from No VED or current keeper.

Tracking a sample of these arrests through the criminal justice system, it was

found that an average ANPR full time equivalent will contribute around 31

offences per annum towards to the Government’s Offences Brought to Justice

(OBTJ) target – this is over three times the rate for conventional policing. If an

ANPR intercept team was deployed by each Basic Command Unit this would

contribute 26,400 additional OBTJs per annum towards the target – around

15% of the Government’s target. Since Laser involves redeploying existing

resources more effectively, this represents little incremental costs and hence

good value for money.

The expansion of Laser 1 to Laser 2 has shown that the results achieved

within a small-scale pilot can be achieved across a much wider cross-section

of forces and that these results can be sustained over time.

7

ANPR has helped pay for itself

Overall the cost recovery process released an additional £1 million in total to

the 23 Laser 2 forces over a nine-month period (to the end of the first financial

year of the pilot). The controls and processes have worked well – while forces

were required to collect additional information and were able to issue new

fixed penalties, there was no evidence to suggest that operational priorities

were distorted – forces achieved comparable arrest rates to Laser 1 where

no cost recovery operated.

Given the focus on recovering monies from Fixed Penalty Notices (FPNs),

the Laser 2 evaluation highlighted the low payment levels associated with

some fines. In particular, the introduction of a £200 fine and 6 penalty points

for no insurance was intended to reduce the burden on courts. However, with

just a 14% payment rate, this has not proved to be the case.

Conclusions

In terms of operation, the use of ANPR intercept teams represents an

innovative approach:

• targeting vehicle documentation enforcement to engage with and

disrupt criminals

• delivered through an intelligence-led piece of technology (an ANPR reader)

• benefiting from officers’ experience (eg observations of vehicle drivers)

• supported by existing policing processes (eg prisoner handling).

On this basis we can conclude that ANPR-enabled intercept teams have

been shown to be an extremely effective means of engaging with criminals.

Laser 2 has built upon the significant success of Laser 1 by proving the

concept across a wider range of forces, over a longer time period and with a

greater level of resource. Using a range of police intelligence and experience,

Laser 2 intercept teams were able to disrupt criminal activity in an efficient and

effective manner, bringing more than three times the number of offences to

justice compared to conventional policing.

While the cost recovery element realised less than 10% of the expenditure

incurred, these monies were important, for example, in helping to improve the

intelligence capability of the ANPR teams and providing part of the administrative

support required. On this basis, we conclude that the cost recovery aspect

contributed to the overall success of Laser 2. The pilot identified a number of

areas where operations could be improved (in particular by having more

accurate data). Once these areas have been addressed, it is expected that

ANPR will be an even more effective policing tool than was shown.

8

Recommendations

The evaluation highlighted a number of recommendations, including:

• Roll-out of Project Laser – Project Laser has proved that ANPR intercept

teams, if used appropriately, can be an extremely effective police tool in

engaging and dealing with criminality in all its forms. There is a strong case

that Laser is rolled out nationally and this roll-out proceeds as rapidly as

possible to ensure that the benefits to police and society are achieved.

Cost recovery can then be used as a means of supplementing local force

expenditure, in particular in the improvement of intelligence and its handling.

• A review of data used for ANPR – the accuracy of the DVLA database in

particular needs to be investigated. There are also substantial variations in the

quality and accuracy of local intelligence databases that require investigation.

There should be more effective use of intelligence at a national and local

level. Further, the pro-active use of MOT and no insurance databases, planned

in the near future, are an important development and should increase the

productivity of the ANPR intercept teams. These should be fully evaluated

in terms of their strengths and weaknesses.

• A national vehicle intelligence data warehouse – other than for the services

provided by PNC, police forces have to operate with a series of local databases

that are copied and shared between forces. This is a time consuming and

ineffective way of operating and is a further example of the lack of joined up

intelligence management highlighted by the Bichard enquiry report. There is

a need for a national data warehouse to hold all vehicle intelligence to be read

in real time by all ANPR users nationally. In turn, this data warehouse would

also hold ANPR reads and hits as a further source of vehicle intelligence,

providing great benefits to major crime and terrorism enquiries. A means to

fund provision of this data warehouse should be urgently sought by Government.

• Deployment management – currently, most ANPR teams are tasked

and deployed from a central location. This can mean, in some areas,

that considerable time is spent travelling to and from ANPR intercept sites.

Clearly, this is not best use of police time and we suggest that consideration

is given to co-locating ANPR intercept teams with BCUs and roads policing

units, as appropriate. Support systems will need to be put in place to ensure

best practice and intelligence is shared and performance monitored as a whole.

9

• A review of level of fines and payment rates – there is an apparent

disconnect between the levels of fixed penalties for the more serious offences

and the penalties that are awarded if the case is taken to court – anecdotal

evidence suggests that in some cases penalties are less severe in court,

both in monetary value and the number of points awarded. This could potentially

damage the effectiveness of the fixed penalty scheme and needs to be

urgently reviewed by ACPO and the Department of Constitutional Affairs (DCA).

• Development of a national ANPR strategy – we recommend that the

Home Office and Department for Transport, working with other Government

departments and key stakeholders, develop a detailed strategy and

implementation plan for ANPR for the next few years.

Table of contents

10

1. Introduction 12

1.1 Context 13

1.2 Evaluation methodology 15

1.3 This report 20

2. Strategic context 22

2.1 Policy context 23

2.2 The drive to make better use of intelligence 26

2.3 The ACPO road policing strategy 29

2.4 The link between vehicle documentation offences and crime 31

3. How Laser 2 ANPR intercept teams operate 36

3.1 Introduction 37

3.2 ANPR deployment 39

3.3 ANPR data sources 41

3.4 When a stop occurs 44

4. Findings: Operational factors 46

4.1 ANPR staff inputs 47

4.2 Team capabilities and support 55

4.3 Location deployment 58

5. Findings: Vehicle stops 60

5.1 ANPR reads, hits and stops 61

5.2 Observation-generated 65

5.3 All vehicle stops (ANPR and observations) 67

6. Findings: Actions taken, property recovered and arrests made 76

6.1 Possible actions taken at a stop site 77

6.2 Vehicle/ person search 78

11

6.3 Arrests 81

6.4 Other actions 94

7. Findings: Database issues 98

7.1 Context 99

7.2 Data sources 100

8. Findings: Cost recovery 106

8.1 Context 107

8.2 Conditions of cost recovery 108

8.3 Factors affecting the introduction of cost recovery 110

8.4 Fixed penalty notices issued and paid 111

9. Findings: ANPR arrest outcomes 124

9.1 Context 125

9.2 Tracking the outcome of ANPR arrests 125

10. Conclusions and recommendations 132

10.1 Conclusions 132

10.2 Recommendations 138

Appendices 142

Appendix A Acronyms 143

Appendix B: Data collection pro forma 144

Appendix D: Data completeness by field 147

Appendix D: Fixed penalty notices included under cost recovery 149

Appendix E: ANPR case studies 151

Appendix F: National ANPR project board memebership 163

Appendix G: Recorded offence guidance 164

Appendix H: References 166

12

In 2002, police forces started to use Automatic Number Plate Recognition

(ANPR) systems together with dedicated intercept officers. These officers

were able to intercept and stop vehicles of interest identified by the ANPR

systems and question the driver and/or passengers as appropriate. The

intention was that targeted enforcement would detect, disrupt and deter

criminal use of the roads. A six-month evaluation of the use of these

dedicated intercept officers (‘Laser 1’) showed the concept to be extremely

effective, achieving arrest rates many times that of conventional policing.

Although these results were encouraging, there was no additional funding

available for the national testing, roll-out and operation of ANPR-enabled

intercept teams. An innovative funding mechanism was therefore required.

Following a submission to HM Treasury, conditional approval was given to

the Home Office to test a cost recovery scheme for dedicated ANPR-

enabled intercept teams. This would allow police to target vehicle

documentation offences and crime in general using ANPR-enabled

dedicated intercept teams, with the activity part-funded through receipts

from fixed penalties issued.

Since 1 June 2003, 23 forces across England and Wales have been

operating dedicated intercept officers part-funded under cost recovery

(‘Laser 2’). This report presents the findings of the evaluation of Laser 2

for the 1 June 2003 to 31 June 2004.

Introduction

13

1.1 Context

1.1.1 Background to the use of Automatic Number Plate Recognition

ANPR is an established technology that enables vehicles observed by

cameras to have their vehicle registration mark (VRM) ‘read’ using pattern

recognition software. When combined with other resources and data,

ANPR can be an extremely powerful tool in:

• Road tolling – for example, the London Congestion Charging Scheme

uses ANPR-enabled cameras to identify vehicles passing in/out of the

congestion charge zone. This information is subsequently used to levy

tolls and to penalise non-payers

• Vehicle tax evasion – for example, the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency

(DVLA) uses ANPR as part of a system to ensure that vehicles on the road

have a current Vehicle Excise Duty (VED)

• Congestion warning – for example, Trafficmaster uses a national network of

ANPR cameras to measure speed between cameras and, from this, identify

areas of the road network that are congested. This is then used to provide

information to drivers.

The police have used ANPR systems at strategic points for a number of

years, for example at ports, tunnels and in the ‘ring of steel’ around the City

of London as part of counterterrorism measures. With the improvements in

ANPR technologies (which have led to increased accuracy of read and the

ability to process images more rapidly) and a reduction in costs of ANPR and

camera equipment, the police have begun to look to ANPR as a proactive tool

to help address volume crime.

1.1.2 Laser 1 – developing the concept

Recognising the potential of ANPR, the Home Office provided each police

force in England and Wales with a mobile ANPR unit and back office facility

in 2002. With this equipment, forces came to recognise that one of the most

effective ways of exploiting ANPR was to use it with dedicated intercept teams,

typically comprising around six police officers operating either on motorcycles

or from cars. These officers could then intercept and stop vehicles identified

by the ANPR system as worthy of interest, and were thus called an

‘ANPR-enabled intercept team’.

Given that the use of ANPR-enabled intercept teams represented a significant

development in policing in terms of using technology and intelligence, the

Home Office Police Standards Unit (PSU) and the Association of Chief Police

Officers (ACPO) decided to undertake a small-scale pilot over a six-month

period (30 September 2002 to 30 March 2003) – ‘Laser 1’.

14

Nine forces were selected to take part in the pilot, reflecting a cross-section

of force types and geographies.

The aim of the pilot was to gather evidence on the operations and impact of

ANPR-enabled intercept teams to inform policy and potential national roll-out.

These teams stopped 39,188 vehicles, arrested over 3,000 persons (of which

only 20% were for driving-related matters) and took a further 45,000 actions.

These included issuing verbal advice or a fixed penalty, or requesting that

vehicle documentation, such as MOT certificate and vehicle insurance, be

presented at a local police station.

An independent evaluation of Laser 1 concluded that:

“ ANPR-enabled intercept teams have shown to be an extremely

effective means of engaging with criminals. Using a range of

police intelligence and experience, intercept teams were able

to disrupt criminal activity in an efficient and effective manner,

achieving arrest rates ten times the national average.”

1

1.1.3 Laser 2 – testing cost recovery

Although Laser 1 provided encouraging results, there was no additional

funding set aside for the national testing, roll-out and operation of ANPR-

enabled intercept teams. However, following a submission to HM Treasury,

conditional approval was given to the Home Office to test a cost recovery

scheme for dedicated ANPR-enabled intercept teams. This would allow police

to target vehicle documentation offences and crime in general, with the activity

part-funded through receipts from fixed penalties issued.

Following discussions at the National ANPR Project Board (membership listed

in Appendix F), it was decided to undertake a more widespread testing of ANPR,

this time (part) funded by cost recovery – ‘Laser 2.’ The specific objectives of

Laser 2 were as follows:

• to demonstrate whether or not ANPR-enabled intercept teams could continue

to make a significant contribution to the detection of a wide variety of crimes

• to demonstrate that the primary motivation behind the additional activity was

to address criminality, not create revenue

• to inform a policy decision regarding whether or not to introduce primary

legislation to allow for the national roll-out of cost recovery

• to identify and disseminate good practice to maximise the effectiveness

of the teams

1

Engaging criminality – denying criminals use of the roads, PA Consulting Group (October 2003)

15

• to demonstrate workable, non-bureaucratic arrangements for recovering the

costs of the intercept teams that did not distort from existing policing priorities

and operations

• to test the rules and guidelines that were prepared for ANPR cost recovery.

All forces were invited by the Home Office and ACPO to participate in Laser 2.

Following submission of cases to the National ANPR Project Board, 23 forces

(including all nine from Laser 1) were accepted onto this further pilot that

started on 1 June 2003.

Part of ANPR enforcement was intended to be funded through receipts from

fixed penalties issued for vehicle documentation offences by the ANPR teams.

The cost recovery element was governed by a number of rules and guidelines,

to which all 23 Laser 2 forces subscribed. The aim of these rules and guidelines

was to ensure the cost recovery element did not distort the way in which ANPR

was used to the detriment of fundamental policy objectives.

The start of Laser 2 also coincided with the introduction of four new fixed

penalties, three of which were particularly relevant to ANPR teams, namely:

• driving without insurance

• driving without MOT certificate (where required)

• not displaying a vehicle excise licence.

Throughout the pilot, the PSU and ACPO supported individual forces by

disseminating good practice and feeding back performance measurement reports.

1.2 Evaluation methodology

1.2.1 Approach

PA Consulting Group (PA) was commissioned by the PSU to undertake an

independent evaluation of the operations of ANPR-enabled intercept teams.

In parallel, a team within the PSU was charged with developing the good

practice guide. In undertaking the evaluation, PA worked closely with this team

to understand practices that worked well and where specific interventions had

been undertaken by PSU. PA also provided information to forces and the PSU

to help identify good practice.

16

The PSU have developed a good practice guide that addresses key issues

around human resources, technologies and operational practices.

The basis for the evaluation was as follows:

• preparation of a data collection model – this recorded key information on

activities undertaken by the intercept teams and the resource requirements

of these teams. The data collection pro formas used as part of this model

are listed in Appendix B

• collation of this recorded information, data cleansing and validation

• briefings and field visits to each of the participating forces to ensure that

data was collected in a consistent manner and to discuss the operation of

ANPR-enabled intercept teams.

1.2.2 Data collection

Operational information was collected weekly from each Laser 2 force.

For each day of operation, this was:

• total ANPR reads and hits

• officer hours (by rank) for:

– ANPR intercept deployment and non-intercept, eg breaks, travelling time

– prisoner handling up to booking in or handing over

– ANPR admin/spreadsheet data input

• for each vehicle stop:

– day, date, time, location and VRM

– trigger database (or observation) and accuracy of database

– property recovered

– actions taken, including number and type of fixed penalties issued and

arrests made

– crime file reference numbers (to allow for tracking of cases)

where relevant

– ethnicity of vehicle driver and arrested persons.

Further information collated from forces on a quarterly basis included:

• headcount numbers of persons involved in the project

• revenue expenditure, including:

– staff salaries and on-costs (training, national insurance, etc) by rank/grade

17

– IT and communication systems, including maintenance, associated with

ANPR activity

– vehicle lease, maintenance and running costs (including fuel)

– consumables and ancillary costs

– leased accommodation (including office and IT equipment if applicable)

• agreed capital expenditure

• the number of fixed penalties issued, what these were issued for and

whether they were paid or whether the case has gone to court

• progress and variation against their operational case, highlighting any

significant variations and seeking permission for any change in expenditure.

1.2.3 Data validation

Every effort was made to improve data quality, including making the data

collection pro forma straightforward to use, hosting seminars with ANPR

project managers to discuss data collection issues, building basic checks

into the data entry model, undertaking random checks of data and ensuring

that data was logically consistent.

However, given the scale of collection (180,543 vehicles stopped and with

over 2 million data items recorded by the 23 forces) it was inevitable that there

would be a number of inconsistencies in data collection. The main areas of

inconsistency were:

• Different coding practices. For example, officers recorded the ethnicity of

the vehicle driver using codes reflecting their own force practice rather than

a national standard.

• Recording practices. For example, because of the variety of make-up of

ANPR intercept teams (see Chapter 4 below), there was some inconsistency

between forces in measuring officer hours input.

Part of the data cleansing process involved identifying anomalies and seeking

to address them almost immediately; with the aim of improving the quality of

data during the pilot period. In practice, after the first month data inconsistencies

tended to be isolated rather than routine and procedures were developed to

automate the data validation.

In spite of these issues, the vast majority of the data appears robust and the

large number of records allows some compelling conclusions to be drawn about

the benefits of ANPR-enabled officers compared to conventional policing.

18

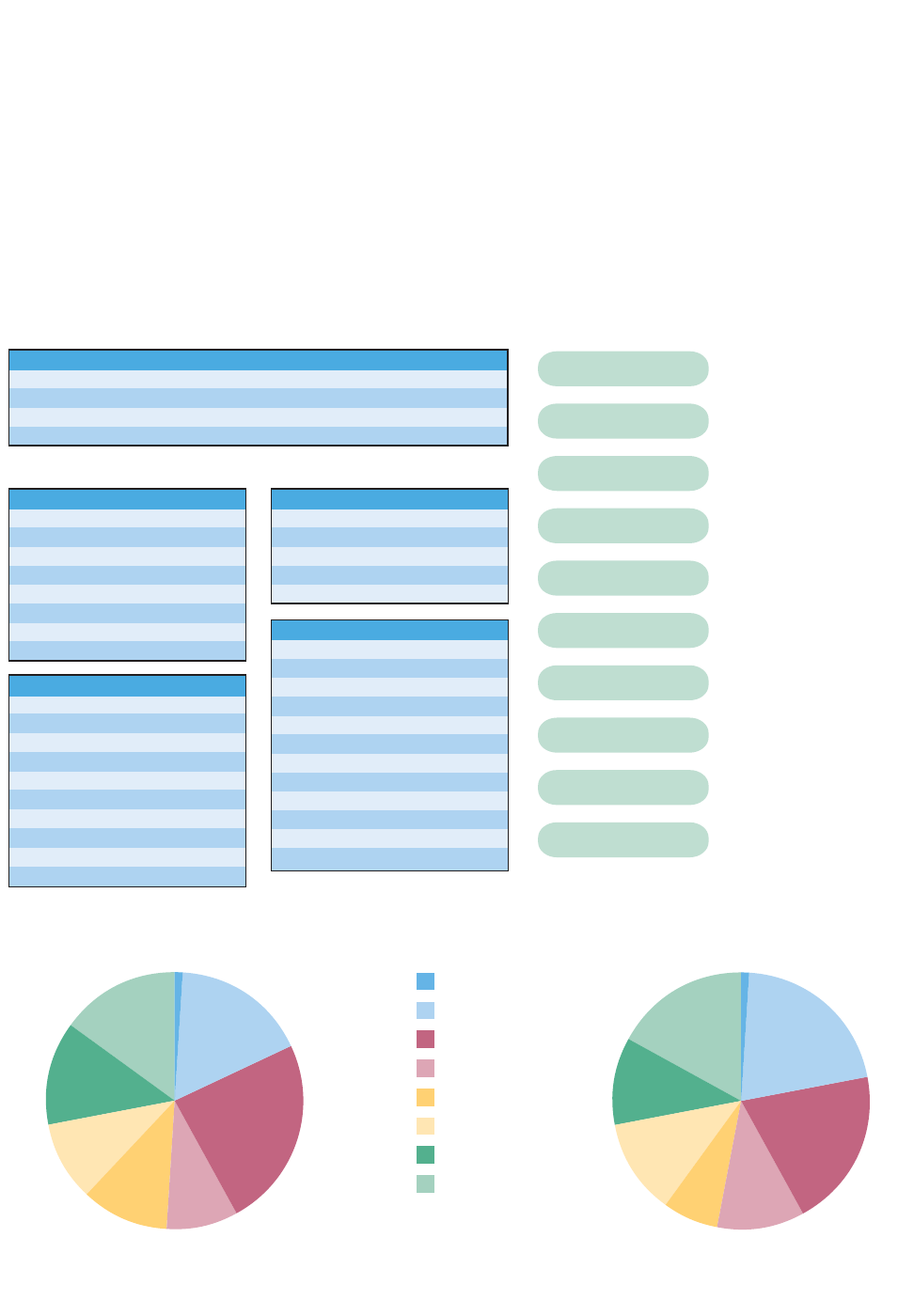

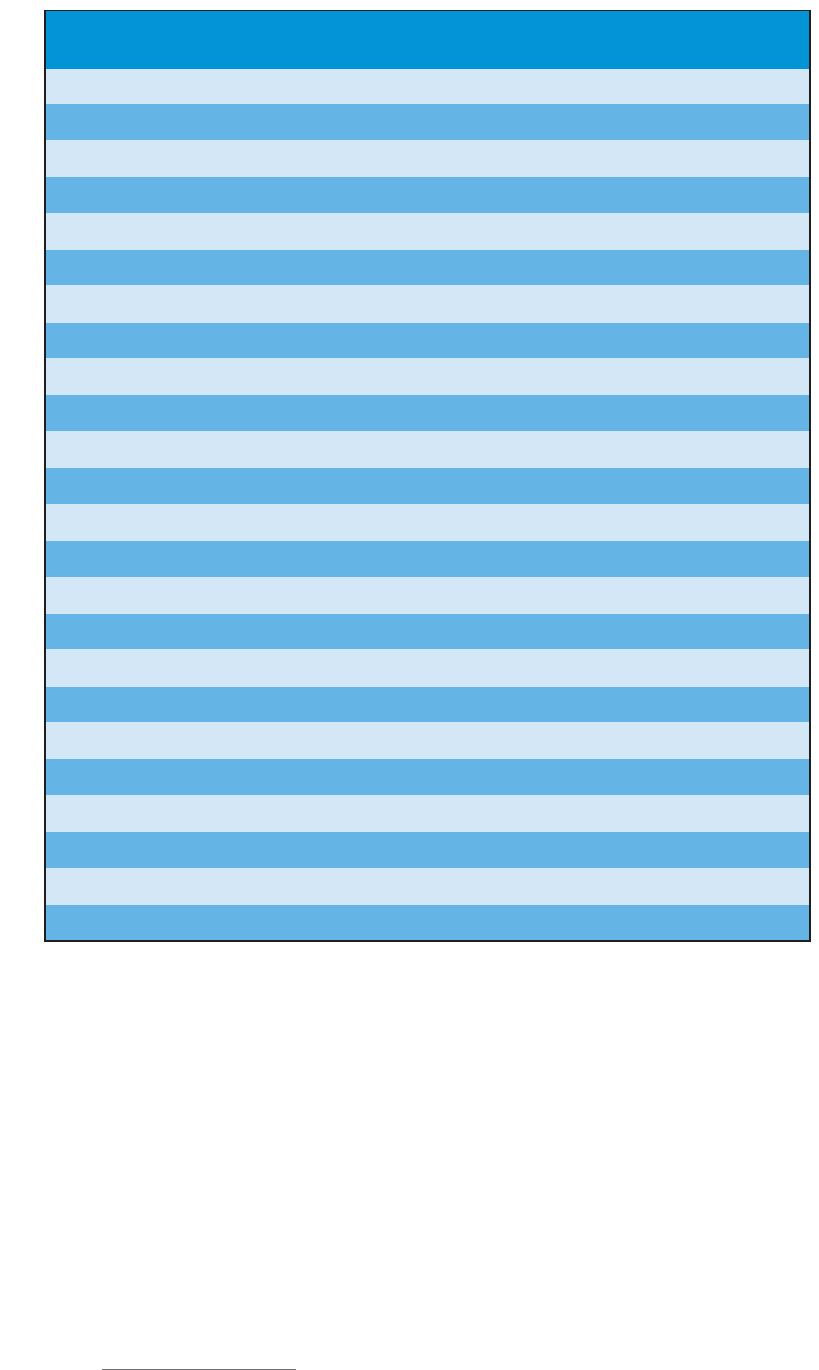

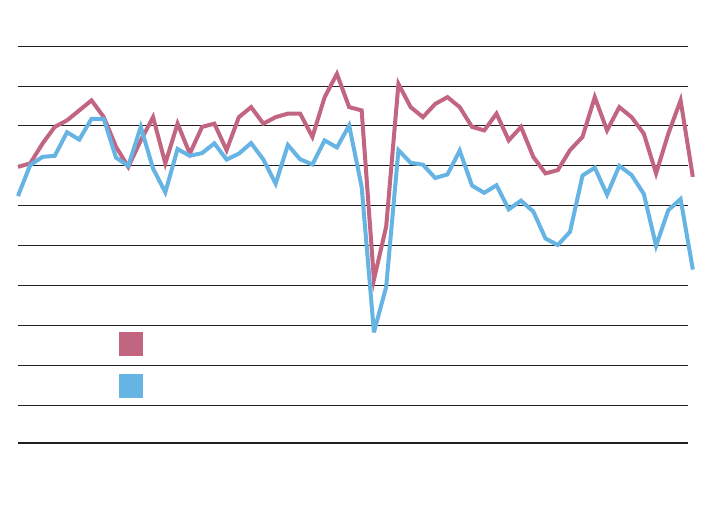

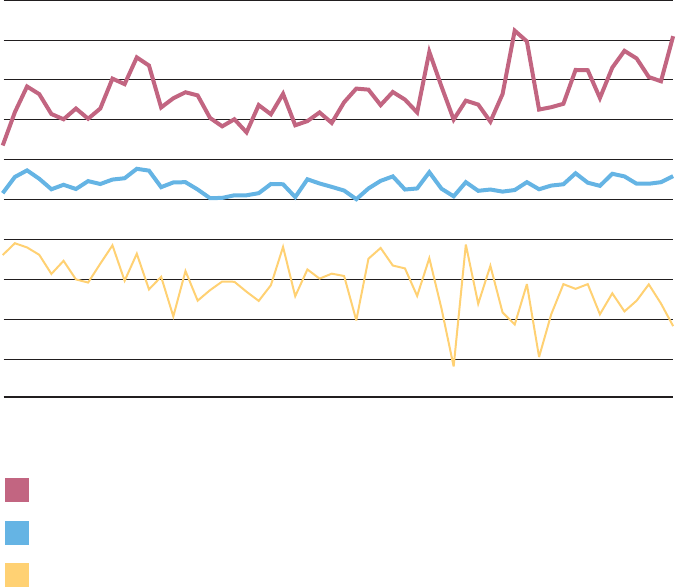

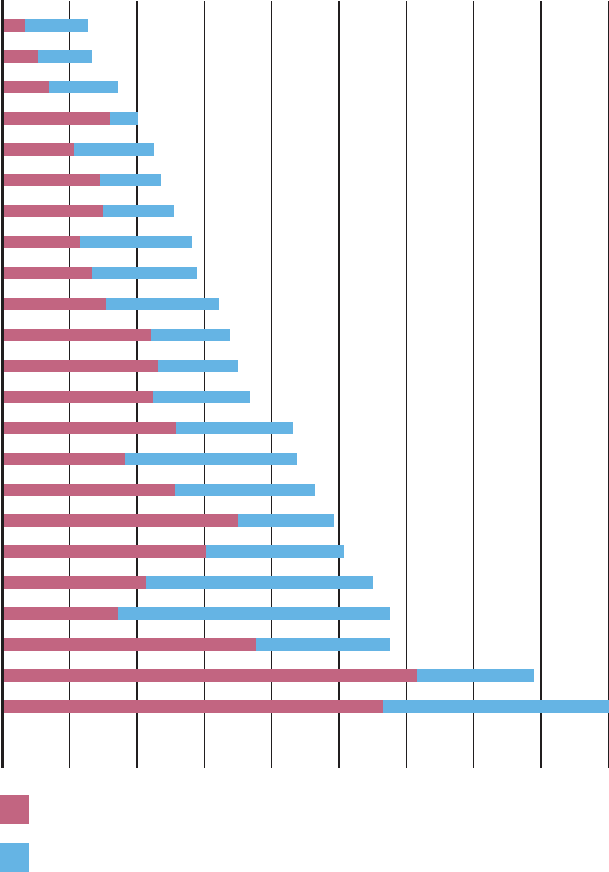

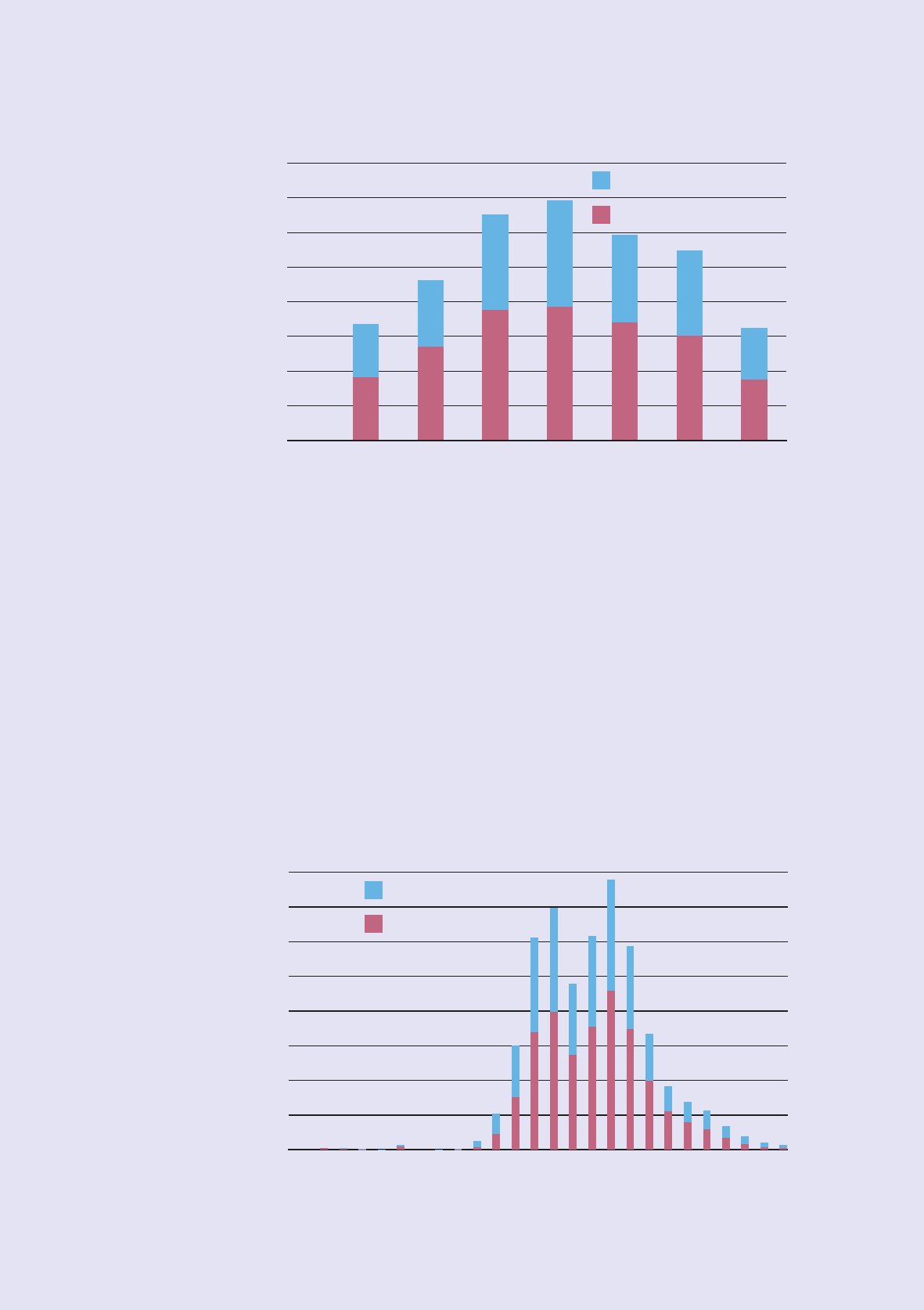

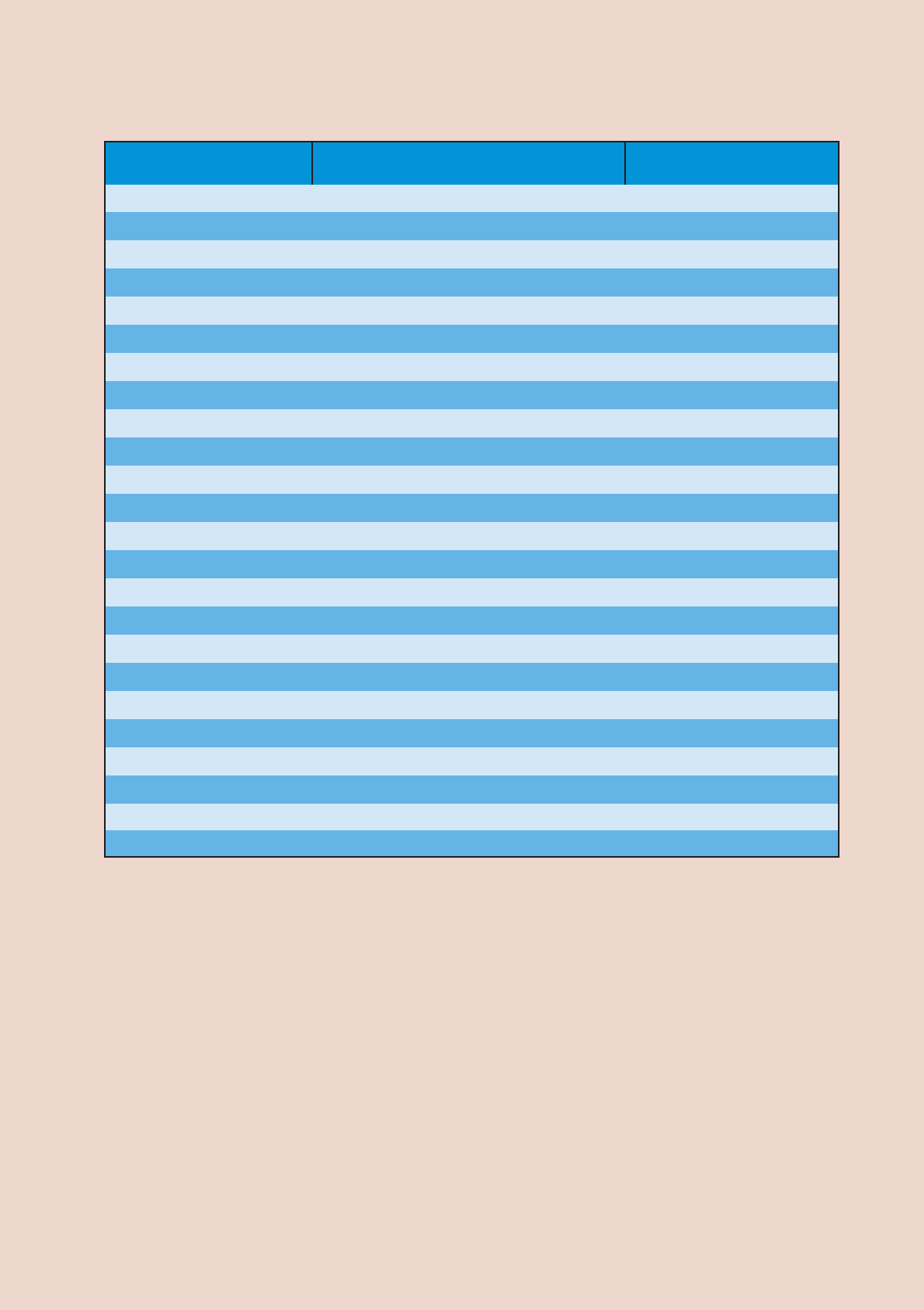

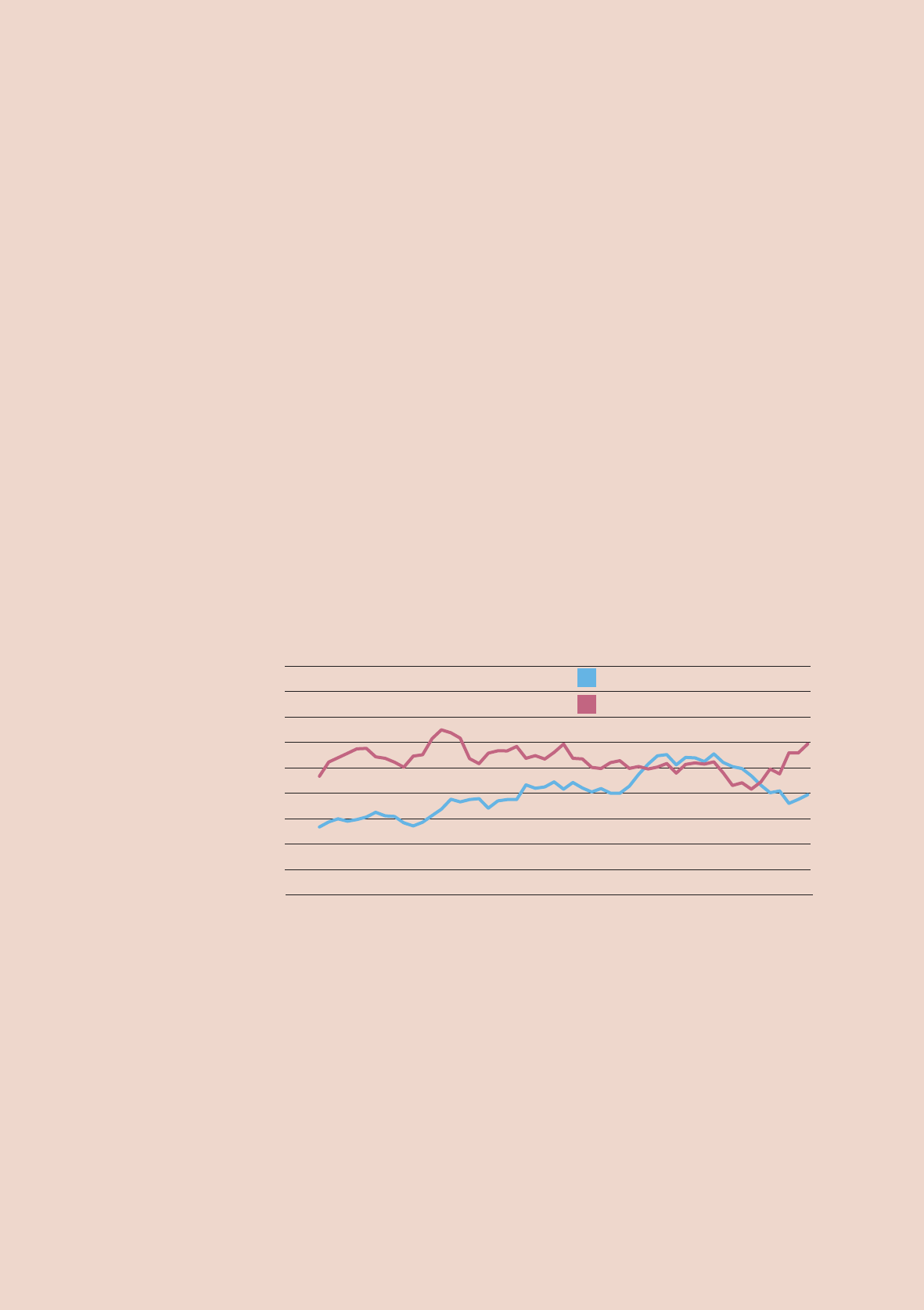

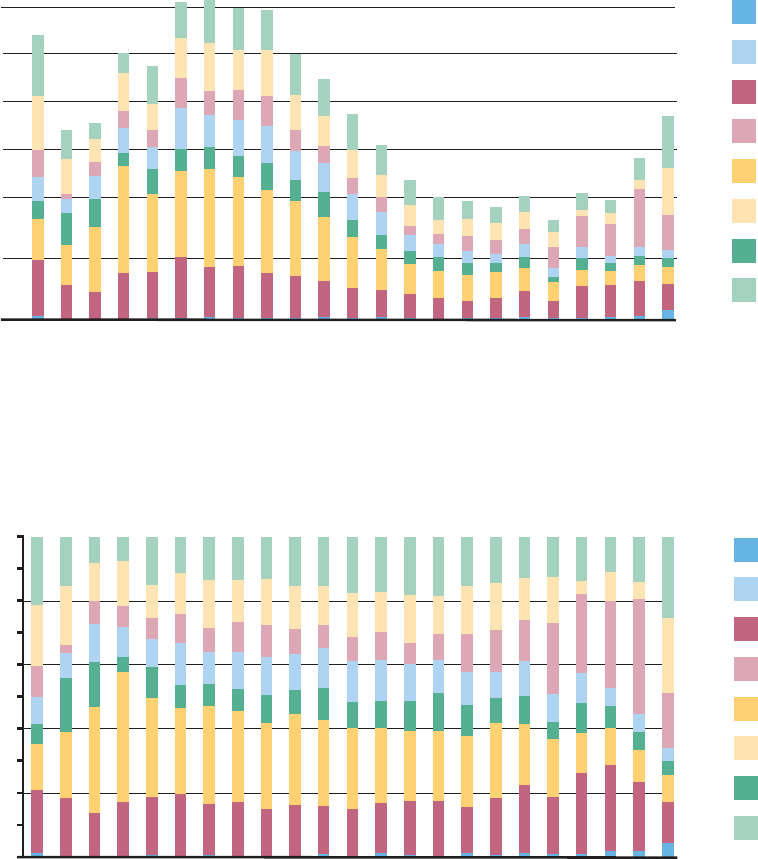

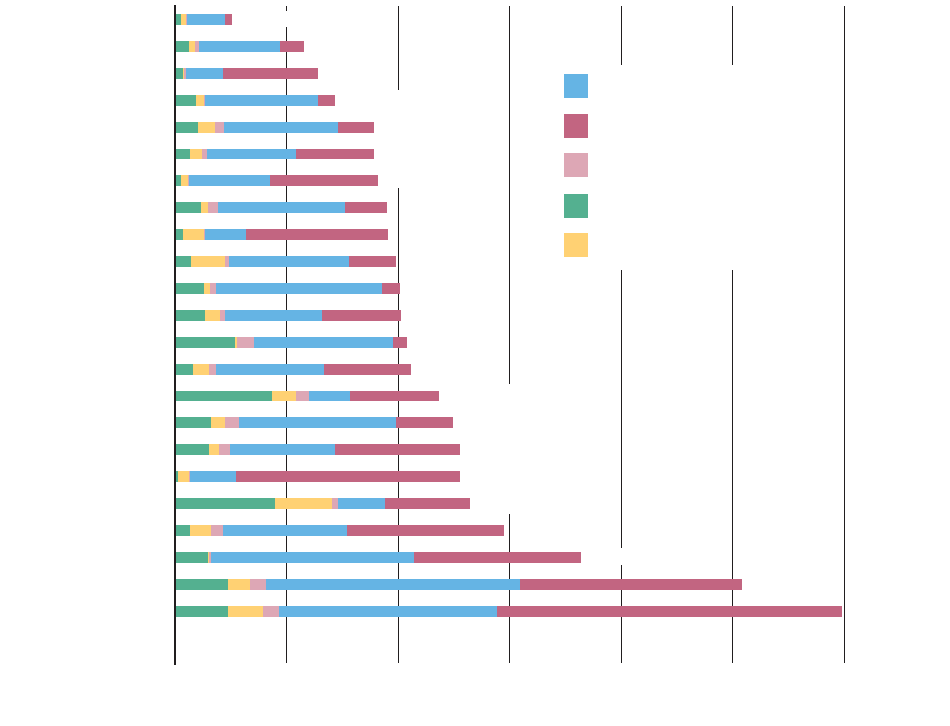

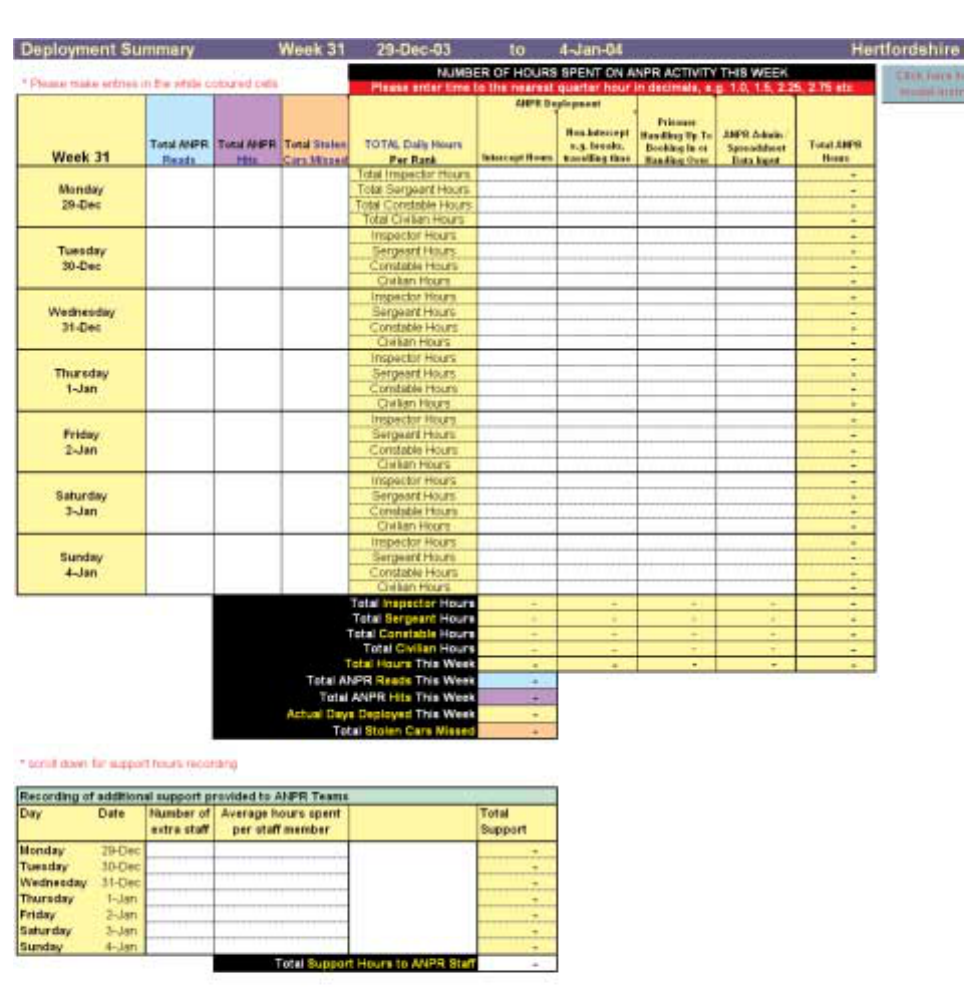

1.2.4 Performance feedback

As part of the data collection cycle the PSU and the 23 forces were provided

with a weekly progress report, one week in arrears. This gave quick feedback

on performance, both relative to other forces and over time, and provided a

means for forces to validate high-level information submitted. The electronic

reports allowed forces to analyse their own data as required – in sufficient time

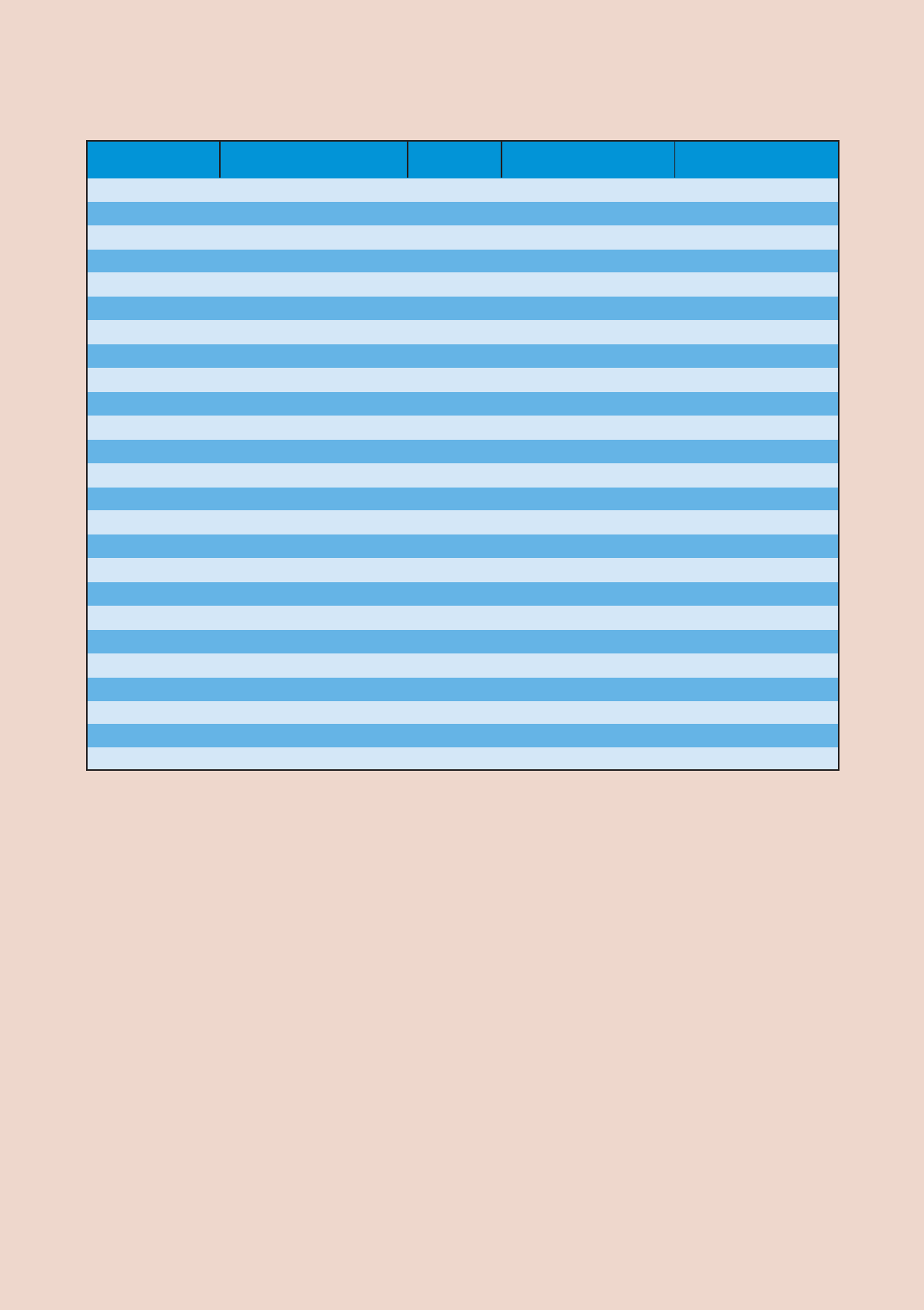

to make changes to operational deployment. A copy of the headline page of

the electronic report is shown in Figure 1.1 below.

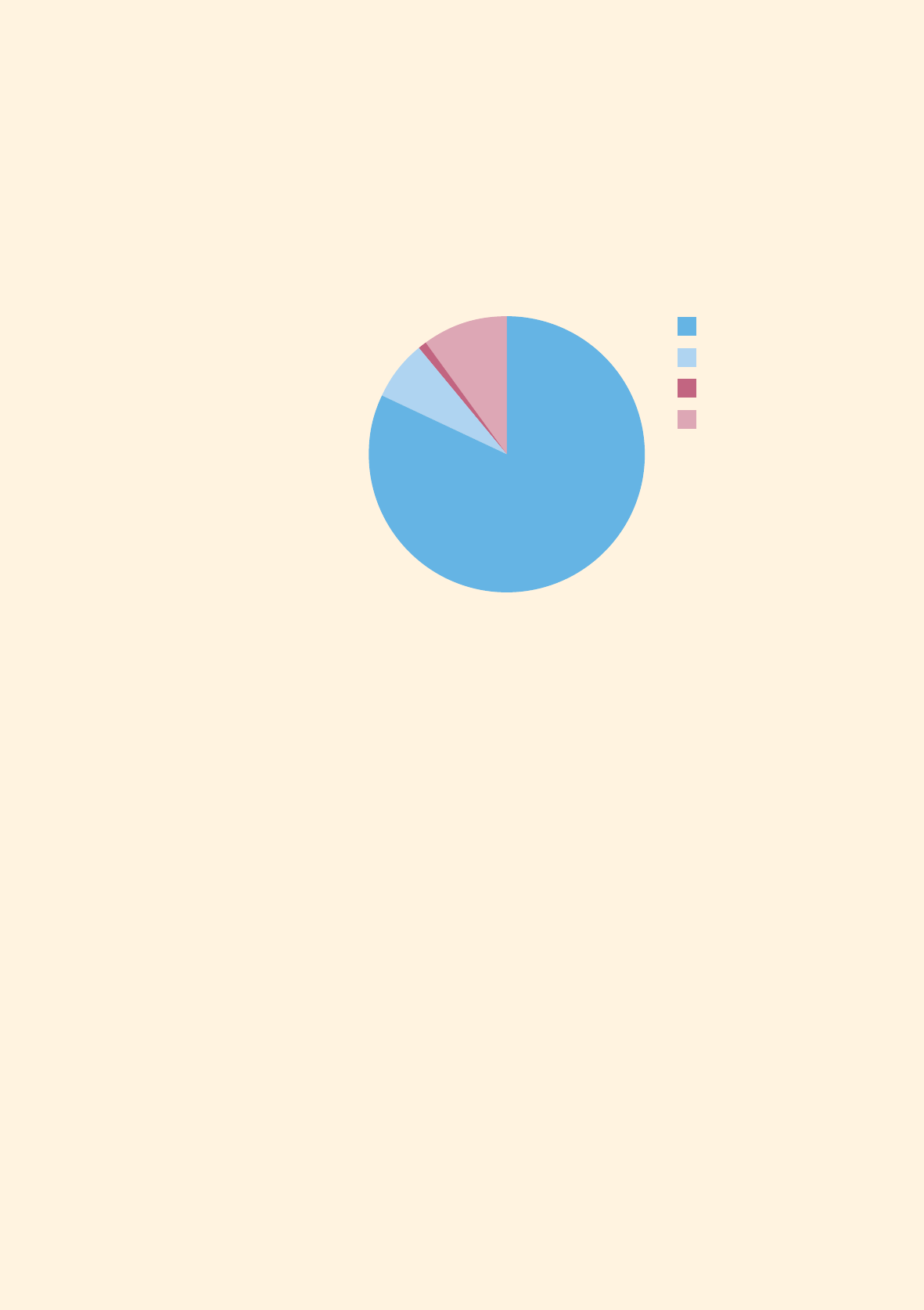

17%

10%

15%

13%

1%

11%

9%

24%

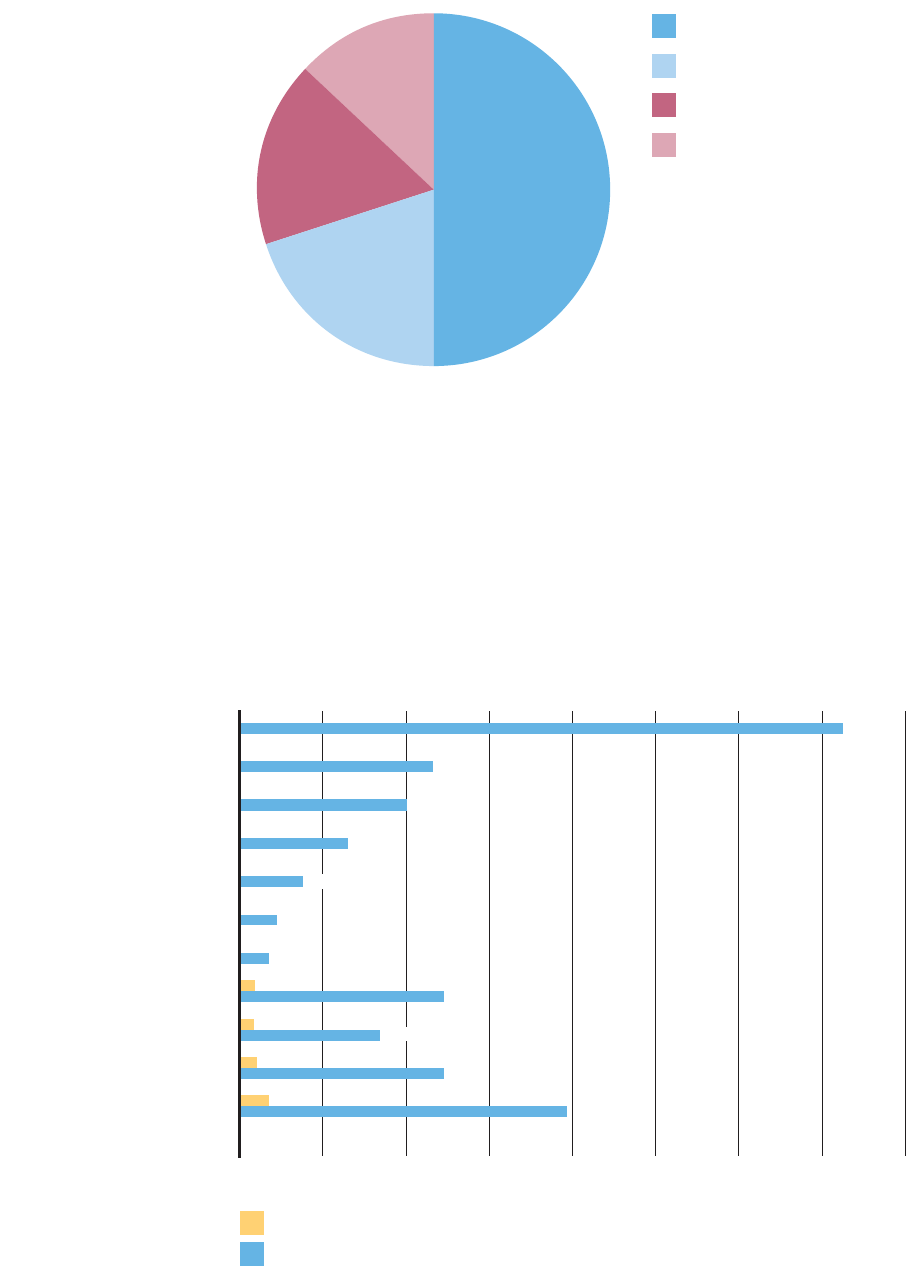

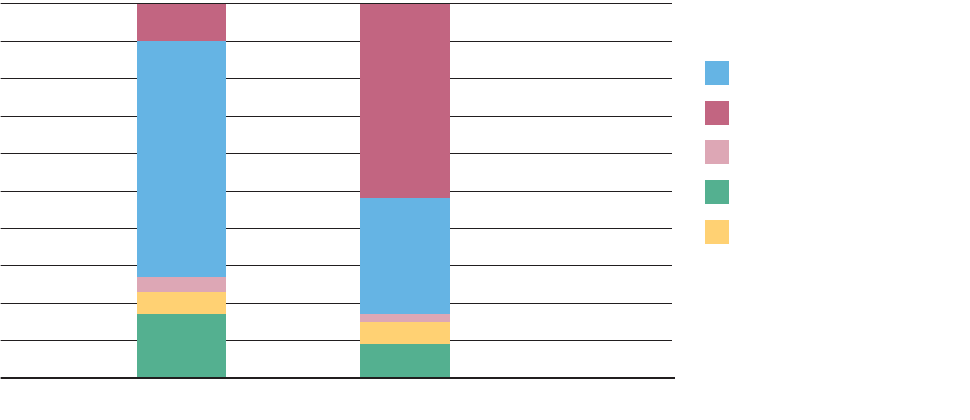

Arrests breakdown in Laser 2

21%

12%

17%

11%

1%

7%

11%

20%

Arrests breakdown for Laser 1

Actions taken

HO/RT1

CLE 2/6 (7)

CLE 2/8 / V62

VDRS / PG9

NEFPN

EFPN

Reported for summons

INTEL log generated

Verbal advice given

No action taken

Arrests breakdown

Robbery

Theft /

burglary

Driving

Drugs

S25

Auto crime

Warrant

Other

58

1,795

2,611

946

1,136

1,064

1,340

1,596

35,580

3,991

14,177

3,009

31,754

7,593

6,117

19,542

15,104

48,916

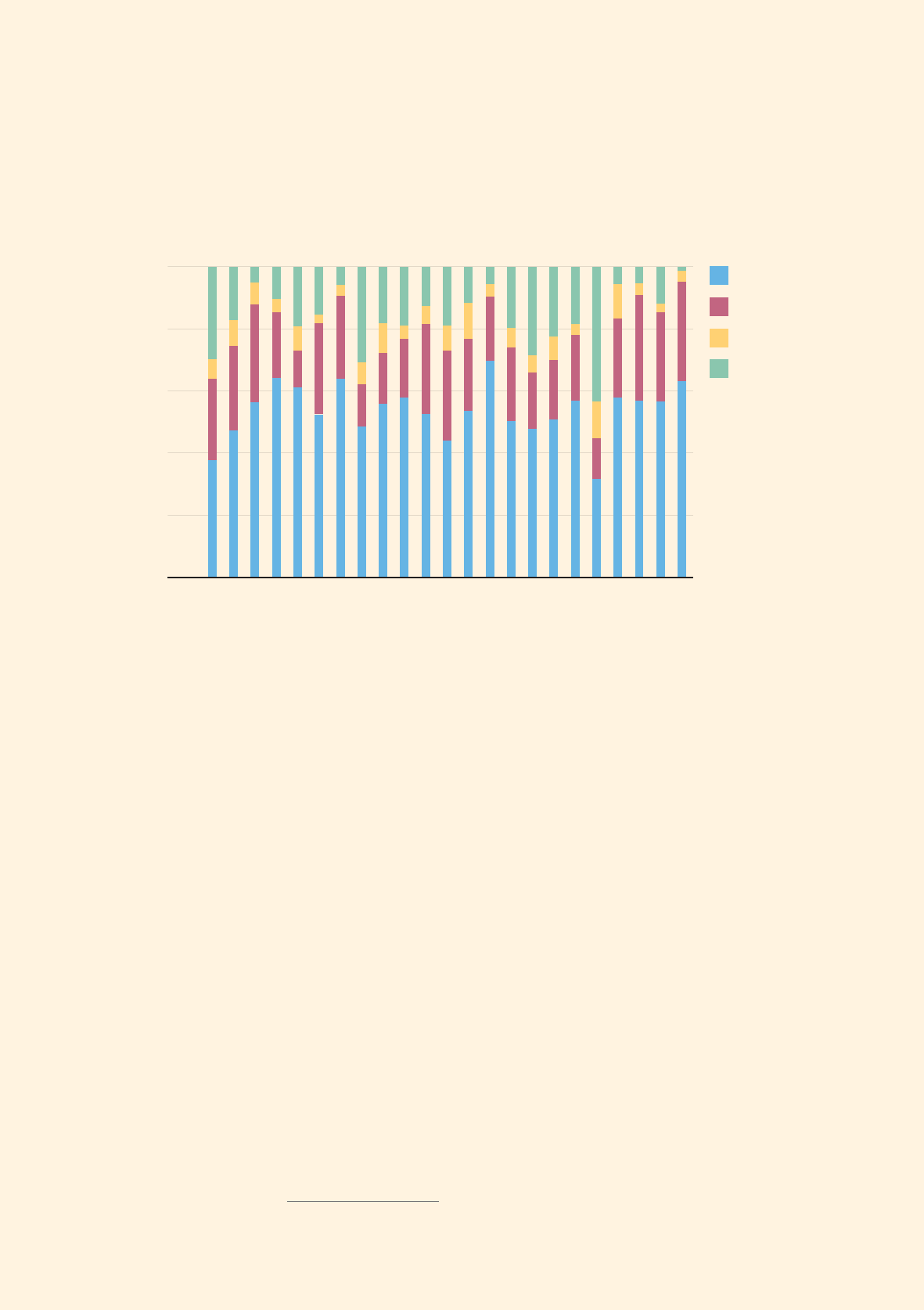

FRNs breakdown

Endorsable: No insurance

Endorsable: Other

Non-end. No MOT

Non-end. No VED

Non-end. Other

4,923

2,112

1,166

18,381

13,646

Property recovery

Stolen vehicle

Stolen goods

Firearms

Drugs

Offensive weapon(s)

Other property

Value of stolen vehicle

Value of stolen goods

Value of drugs

Total property recovered

874

333

8

589

159

282

£5,671,304

£421,453

£381,384

£6,474,140

Overview

Number of stops

Number of arrests

Fixed penalty notice

Pilot arrests per FTE

136,857

10,546

40,228

95

Staff-days on intercept duty

Staff-days travel to intercept

Staff-days prisoner handling

Staff-days spent on admin

3,657

1,661

414

1,100

Detailed weekly view

Arrests / FTE

Total arrests

FPN targets

FPNs issued

Deployment time

Old summary view

Arrests / FPNs per 100 stops

Arrests / FPNs per 100 hours

Stops

Click here to look how each force

is performing on a weekly basis

Click here for the LASER 2 “Arrests

per full time equivalent” chart

Click here to view comparison of

total arrests and breakdown by force

Click here to see how each force is

performing against its FPNs target

Click here to view all FPNs issued

by force. Breakdown also provided

Click here to see how force

deployment times compare

Click here to see weekly results

in the original format

Click here to see arrests and

FPN performance per 100 stops

Click here for arrests and FPN

performance per 100 intercept hours

Click here to compare the volume

of stops achieved by each force

Robbery

Theft / burglary

Driving

Drugs

S25

Auto crime

Warrant

Other

Figure 1.1: Weekly reporting tool provided to Laser 2 forces (front page only)

19

For the 14 additional forces joining Project Laser in June 2003, there was a

significant project mobilisation stage. In practice many of these forces were

unable to deploy their intercept teams for the first weeks of the pilot, and

when they were deployed, they were still developing their operational strategy.

Moreover, the data collection process took time to ‘bed-down’.

In recognition, the National ANPR Project Board extended the period covered

by the evaluation to a 13 month period to allow analysis of one year’s good

quality data. Thus in reviewing these findings a number of points are worth noting:

• While ANPR is an established technology, for many forces the use of

ANPR-enabled intercept teams represented a new way of working. As such,

operations changed to reflect feedback from the field. Also most forces used

the pilot as an opportunity to develop the way they used ANPR and varied

the way they deployed intercept teams in response to operational experience.

These evaluation results thus do not cover a ‘steady state’ period – for

example this evaluation report shows that performance improved over

the year for the 14 forces new to ANPR.

• Weeks 30 and 31 covered the Christmas period and operations were

much reduced.

• During January 2004, forces were invited to submit operational cases for June

2004 to May 2005. The majority of forces chose to continue ANPR operations

as before, though some forces re-evaluated and restructured their ANPR

operations to reflect local operational needs (eg Avon and Somerset included

prisoner handling as a core function of the ANPR team, while Leicestershire

devolved ANPR operations to Basic Command Unit level).

1.2.6 Contribution to Narrowing the Justice Gap

Laser 1 had shown that ANPR was a particularly effective tool for targeting

police resources, producing arrest rates many times those normally achieved.

Laser 1, however, had not collected information on the outcome of these

arrests. This information was key to evaluating the potential impact of ANPR

on the justice system and the Government’s target for the number of Offences

Brought To Justice (OBTJ) programme.

Following a presentation to the Narrowing the Justice Gap (NJG) taskforce,

we were asked to review the outcome of these ANPR-generated arrests and

to estimate their contribution to the Government’s target. As part of this exercise,

Laser 2 forces were asked to provide information on the outcomes of the arrests

they made between June 2003 and August 2003.

20

A number of forces were able to provide this information from their existing

information systems. While the results of this analysis have already been

presented internally to the Narrowing the Justice Gap taskforce, the main

conclusions are also re-presented here for the sake of completeness.

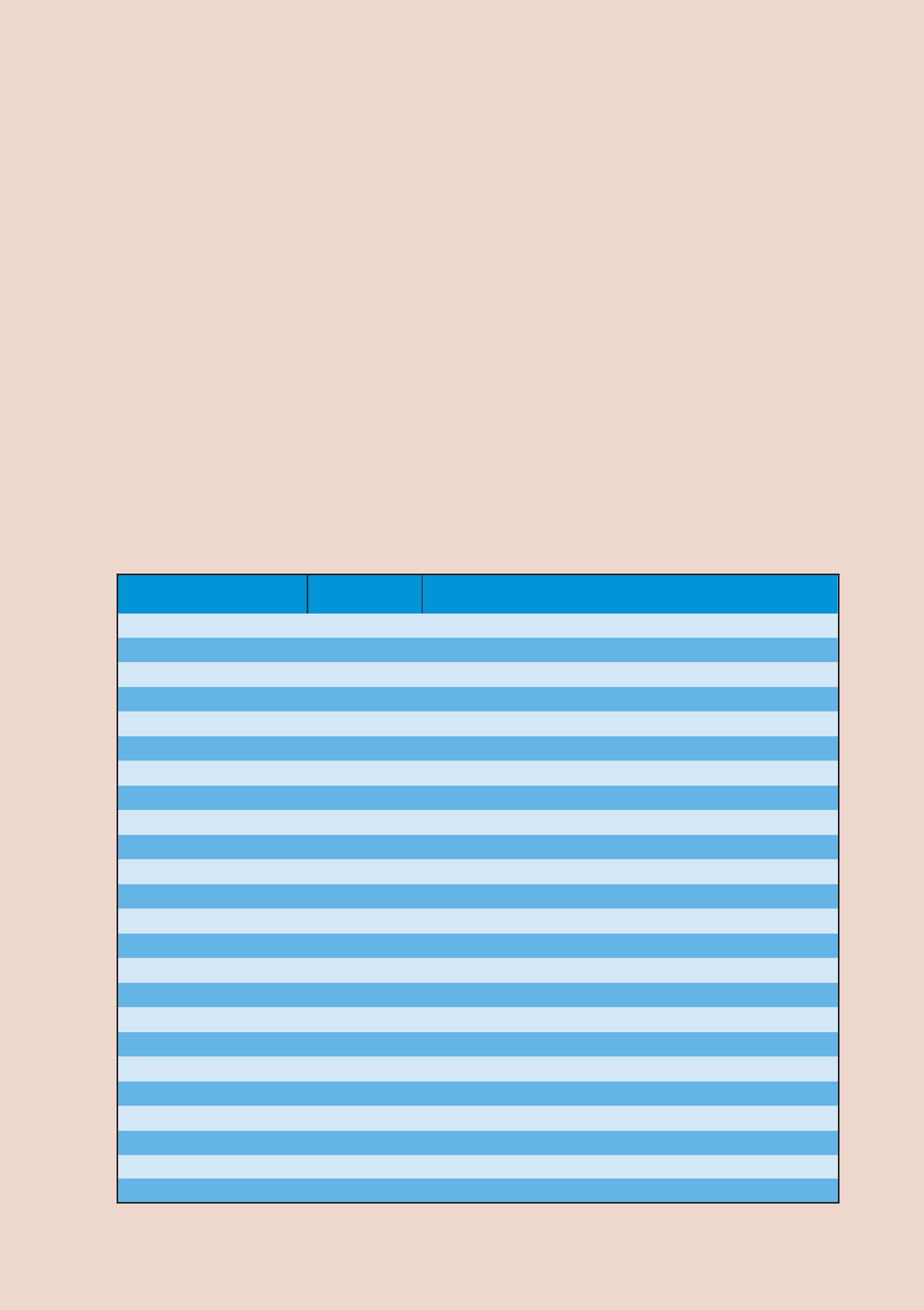

1.3 This report

This report presents the findings of PA’s evaluation of Laser 2. The purpose

of this evaluation was to explore the validity of ANPR-enabled intercept teams,

not to assess relative performance of intercept teams between forces. Results

presented have therefore been aggregated across the 23 forces, though where

appropriate these have been broken down by force. In terms of coverage, the

diagram below sets out the difference between this report and the evaluation

of Laser 1.

This report is set out in nine further chapters as follows:

• chapter 2 gives policy background of ANPR-enabled intercept teams

• chapter 3 provides an overview of Laser 2 ANPR-enabled intercept teams

and how they operate

• chapter 4 outlines operational staff inputs used during the pilot

• chapter 5 identifies ANPR reads, hits and stops, that is the number of VRMs

read by the ANPR units, the number of times these reads led to a match with

an intelligence database, and the number of vehicles of interest stopped by

the intercept teams

• chapter 6 examines database issues

• chapter 7 looks at the actions taken, the property recovered and arrests

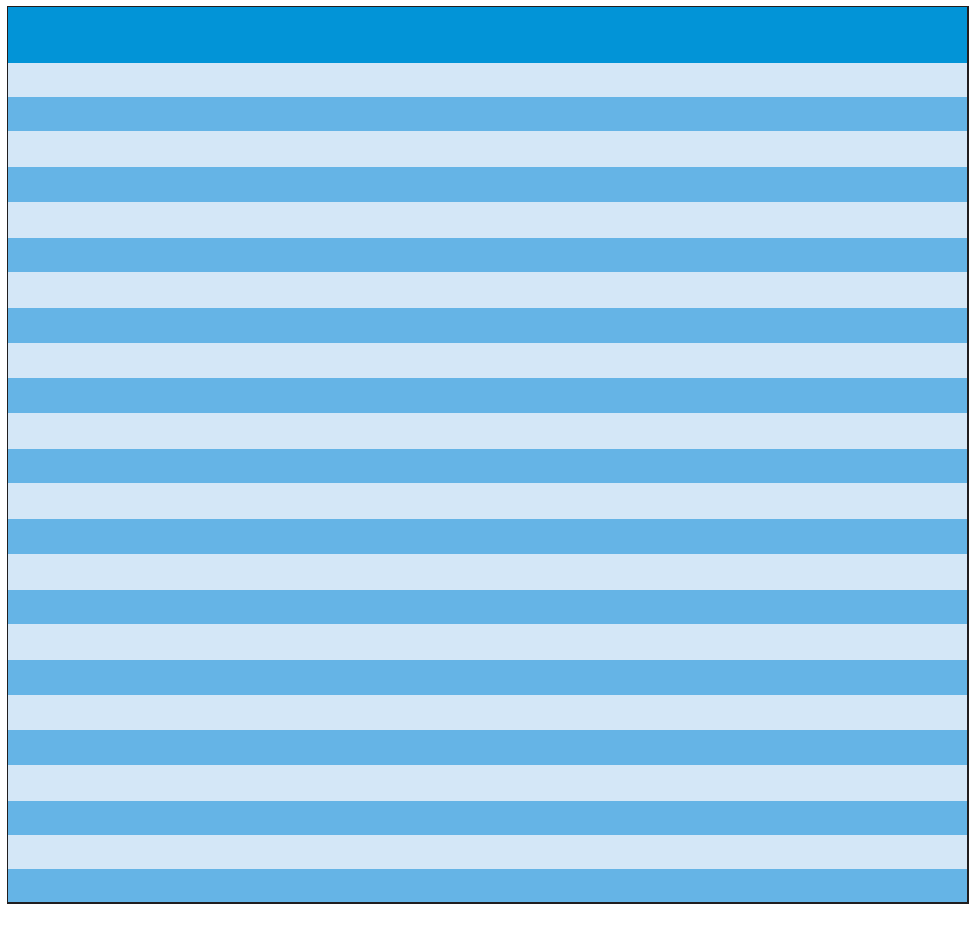

Avon and Somerset Constabulary

Cambridgeshire Constabulary

Cheshire Constabulary

City of London Police

Cleveland Police

Greater Manchester Police

Hampshire Constabulary

Hertfordshire Constabulary

Kent Constabulary

Lancashire Constabulary

Leicestershire Constabulary

Lincolnshire Constabulary

Merseyside Police

Metropolitan Police Service

North Wales Police

North Yorkshire Police

Northamptonshire Police

Northumbria Police

Nottinghamshire Constabulary

Staffordshire Police

Warwickshire Police

West Midlands Police

West Yorkshire Police

Avon and Somerset Constabulary

Greater Manchester Police

Kent Constabulary

Metropolitan Police Service

North Wales Police

Northamptonshire Police

Staffordshire Police

West Midlands Police

West Yorkshire Police

Approximately 70 full time equivalents

6 months data

No cost recovery

No evaluation of impact on Justice Gap

No data on ethnicity

9 forces

Approximately 192 full time equivalents

13 months data

Cost recovery

Evaluation of impact on Justice Gap

Data on ethnicity

23 forces

Laser 1 evaluation Laser 2 evaluation

21

• chapter 8 looks specifically at the cost recovery aspect, including the cost

of ANPR operations and the fine penalties recovered

• chapter 9 examines the outcome of ANPR arrests and presents the potential

contribution that ANPR could make to the Government’s target for Offences

Brought to Justice

• chapter 10 sets out the evaluation conclusions in terms of the original

objectives for the pilot and on this basis makes a number of recommendations.

This report also has eight appendices as follows:

• appendix A lists the acronyms used in this report

• appendix B shows the data collection pro forma as used by the

intercept teams

• appendix C presents a summary of data completeness by field

• appendix D lists all Fixed Penalty Notices that were included within this pilot

• appendix E presents some ANPR case studies from forces as presented on

their websites

• appendix F lists the representation on the National ANPR Project Board

• appendix G provides outline guidance on recorded offences

• appendix H lists documents referenced throughout the report.

In all the graphs and tables in this report, Week 1 refers to the first week of

the evaluation period, ie June 1 2003. Weeks 30 and 31 therefore covered

the Christmas/New Year period.

For some of the analysis column totals may differ slightly from the total

displayed due to rounding.

Officers of the 23 forces involved in Laser 2 have provided the data used to

compile this report (on a weekly basis).

22

This section of the evaluation sets out the strategic context for the operation

of ANPR-enabled intercept teams. This covers four broad areas.

First, part of the Government’s vision for the criminal justice system is to

bring an additional 150,000 offences to justice in 2008 than is currently the

case and to share information within the system more effectively to reduce

inefficiencies. Within their strategy, the Government identifies ANPR as a

key means to improving police effectiveness [Section 2.1].

Second, the introduction of the National Intelligence Model within the

Police Service and the findings of the recent Bichard inquiry provides a

strong focus for police to ensure information is fully researched, developed

and analysed to provide intelligence for policing and police managers

across forces [Section 2.2].

Thirdly, the ACPO Road Policing Strategy sets out a clear objective of

detecting, disrupting and challenging criminal use of the roads. To achieve

this it is planned that police will make full use of modern technology, in

particular that approximately 2,000 officers will deliver an intercept capability

ANPR. This equates to a police intercept team in every Basic Command

Unit area [Section 2.3].

Strategic context

23

To support this ACPO have developed an ANPR strategy for the police.

At present, however, there is no complementary strategy for use ANPR

across other Government bodies, including DVLA, DfT, Customs & Excise,

the Highways Agency, VOSA, and the ports authorities [Section 2.3].

Finally, this section identifies that there is substantial evidence that the

pursuit of vehicle documentation offences will lead to more serious crimes

being detected and that relatively little police time is spent undertaking

proactive vehicle documentation checks. As such, there is an opportunity

being lost to address wider criminal issues. If this were addressed by

means of ANPR-enabled intercept teams, this would also meet the public’s

desire to see more ‘officers on the street’ and more action taken against

illegal drivers [Section 2.4].

2.1 Policy context

In the recent strategic plan for the Criminal Justice System

2

the Government

sets out a vision for the criminal justice system for 2008. This vision is built

around five key objectives:

•

“The public will have confidence that the Criminal Justice

System is effective and that it serves all communities fairly.

• Victims and witnesses will receive a consistently high standard

of service from all criminal justice agencies.

• We will bring more offences to justice through a more modern

and efficient justice process.

• Rigorous enforcement will revolutionise compliance with

sentences and orders of the court.

• Criminal justice will be a joined up, modern and well run service,

and an excellent place to work for people from all backgrounds.”

3

2

Cutting Crime, Delivering Justice: A Strategic Plan for Criminal Justice 2004-08, Home

Office/DCA (July 2004)

3

Ibid (July 2004), p9-10

24

In terms of the primary objective of an effective criminal justice system,

the strategic plan sets out the Government target of bringing 150,000 more

offences to justice in 2008 and states:

“We will raise the detection rate from 19% to at least 25%, by

improving police effectiveness and deploying new technology,

including enhanced DNA testing and Automatic Number Plate

Recognition systems, across the country to target criminals

more effectively.”

4

The strategic plan also identifies the need for better intelligence and

information-sharing across the criminal justice system. It highlights that there

is no single data source to identify individuals who may be wanted by a

number of police forces and courts for fine arrears, failing to appear in court

or probation breaches. This means that agencies are often pursuing the same

offender separately for breaches of different types of warrant. The police may

arrest someone and bail them without knowing about outstanding warrants for

them. Equally, unknown to a court, a defendant appearing in front of them may

have failed to answer charges elsewhere or have other outstanding fines or

community punishments. This leads to poorly-informed decisions, frustration

on behalf of the professionals involved and unnecessary costs; it also helps

undermine public confidence in criminal justice.

To address this, the strategic plan sets out a key change in information

sharing, namely:

“We are giving direct access to the Police National Computer to

all Magistrates’ Courts Committees by Autumn 2004. This will

enable warrants to be entered promptly onto the system so

police are aware of and can act on them. We will also link this

into the ANPR system so that offenders wanted on warrants can

be identified when their car is spotted by an ANPR camera.”

5

4

Ibid (July 2004), p10

5

Ibid (July 2004), p42

25

The Government’s commitment to tackling vehicle crime and, in particular,

addressing the problem of uninsured driving was outlined in the Government’s

response to the publication of the Greenaway report in August 2004

6

. The Road

Safety Minister David Jamieson announced that the Government will:

• give the police the power to seize and, in appropriate cases, destroy vehicles

that are being driven uninsured

• link the DVLA’s Vehicle Register and the Motor Insurance Databases,

allowing police to know which vehicles on the road are uninsured

• allow fixed penalties for people who ignore reminders that their insurance

has expired.

The DfT also wants to see and is discussing with relevant stakeholders:

• concerted action by insurance companies to continue to improve the Motor

Insurance Database

• simpler and clearer notification procedures so that no one is in any doubt

when their insurance expires

• automatic reminders sent out to those motorists who forget to insure on time.

David Jamieson, Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State in the Department

for Transport said:

“ I very much welcome Professor Greenaway’s report. We know

that lawabiding motorists are fed up with paying the price for the

small, hard core of antisocial motorists who drive uninsured, often

in untaxed or unsafe vehicles.

The Government is determined to tackle head on the menace

of uninsured driving. That is why I have announced today that

we plan to give the police the power to seize and destroy

vehicles that are being driven illegally and to increase police

powers to use new technology to make detection and

enforcement more effective.

We are also working closely with the insurance industry to

improve detection of drivers who fail to insure their vehicles

and to raise awareness of the need for motor insurance.

The message to the small hard core of antisocial motorists

who drive without insurance is clear – uninsured driving

is unacceptable.”

7

6

Uninsured Driving in the United Kingdom, Professor David Greenaway (July 2004)

7

David Jamieson, DfT press release 11 August 2004

26

Caroline Flint, Parliamentary Under-Secretary of Stete in the Home Office, added:

“ Uninsured driving victimises the law-abiding motorist.

This report gives a sensible way forward to tackling the problem

and across Government we will work hard to take forward its

recommendations. We want to ensure that the police and courts

have the powers they need to tackle offenders and that they can

use them effectively.

We are also working closely with the police to ensure that the

hugely successful Automatic Number Plate Recognition system

is used as effectively as possible to target those who flout the

law and drive without insurance.”

8

Finding 1. The Government views ANPR as a key tool for bringing

more offences to justice and to identify and pursue the estimated

1 million motorists that drive without insurance as well as those

wanted on warrant.

2.2 The drive to make better use of intelligence

The use of ANPR-enabled intercept teams is an excellent example of an

intelligence-led policing tool. This section looks at the current drivers for

making best use of police intelligence. This applies at both a National and

European level, with ANPR expected to be a key part of policing international

borders and sharing intelligence across European states as part of the

Schengen Acquis.

2.2.1 The National Intelligence Model (NIM)

In the context of the police reform agenda, the NIM is ‘A Model for Policing’

that ensures that information is fully researched, developed and analysed to

provide intelligence that police managers can use to:

• provide strategic direction

• make tactical resourcing decisions about operational policing

• manage risk.

It is important to note that the NIM is not just about crime and not just

about intelligence – it is a model that can be used for most areas of policing.

It offers, for the first time, the realisable goal of integrated intelligence in

which all forces and law enforcement agencies play a part in a system

greater than themselves.

8

Caroline Flint, DfT press release 11 August 2004

27

Launched by the National Criminal Intelligence Service (NCIS) and adopted by

the ACPO in 2000, the government placed the NIM at the centre of the police

reform agenda. The model has been designed to impact at three levels of

business: local, cross border and serious and organised crime:

• Level 1 – Local issues – usually the crimes, criminals and other problems

affecting a Basic Command Unit or small force area. The scope of the crimes

will be wide ranging from low value thefts through to serious offences such as

murder. The handling of volume crime will be a particular issue at this level.

• Level 2 – Cross border issues – usually the actions of a criminal or other

specific problems affecting more than one basic command unit. Problems

may affect a group of basic command units, neighbouring forces or a group

of forces. Issues will be capable of resolution by forces, perhaps with support

from the National Crime Squad, HM Customs and Excise, the National

Criminal Intelligence Service or other national resources. Key issues will be

the identification of common problems, the exchange of appropriate data and

the provision of resources for the common good.

• Level 3 – Serious and organised crime – usually operating on a national and

international scale, requiring identification by proactive means and response

primarily through targeting operations by dedicated units and a preventative

response on a national basis.

In the context of ANPR-enabled intercept teams, their primary role is to

address level 1 criminality, though clearly they have a potential role in tackling

level 2 and 3 criminality. For example ANPR units can gather intelligence on

vehicle movements and the deployment of intercept teams on strategic roads

and could potentially detect and disrupt cross border movement of criminals.

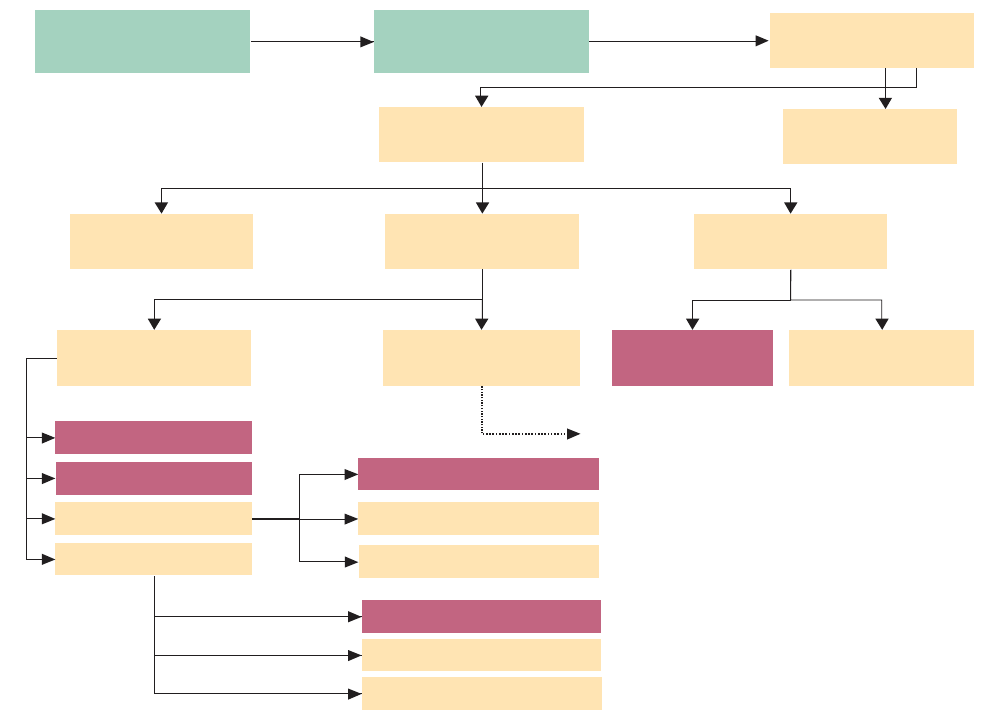

PSU have developed a process map of how ANPR contributes to NIM.

This is explained in full in the good practice guide and summarised in

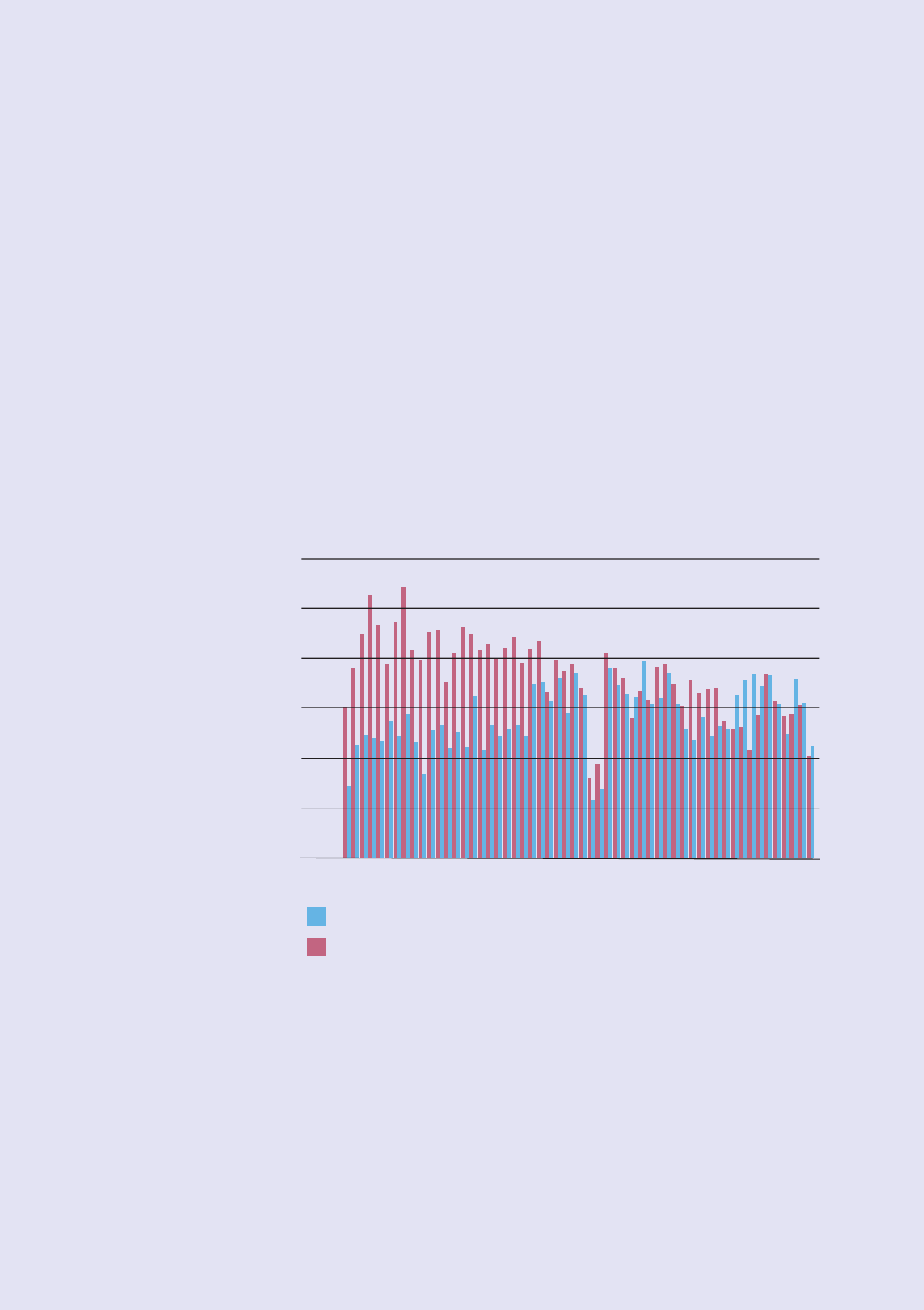

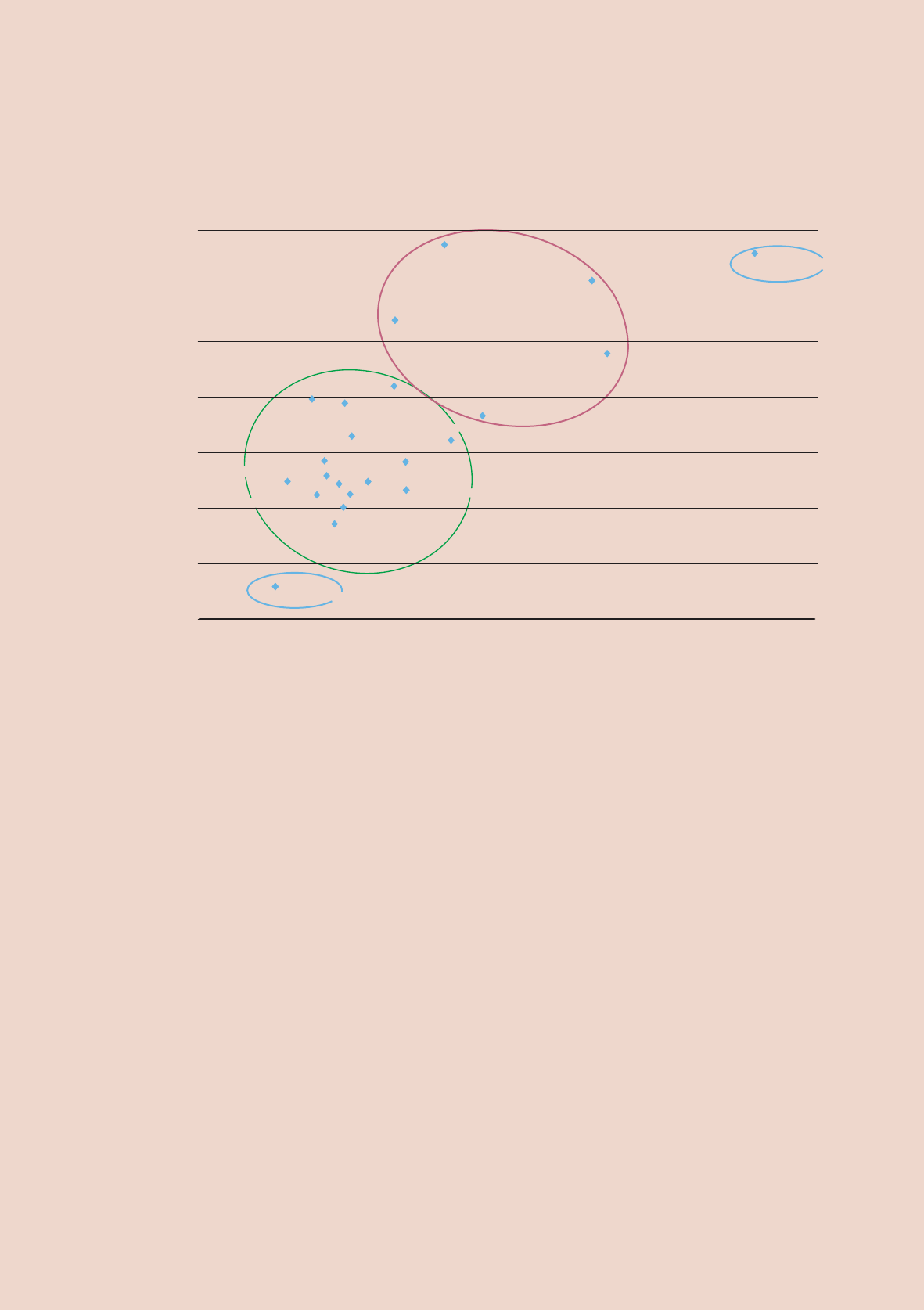

Figure 2.1 overleaf.

28

2.2.2 Policing Bureaucracy Taskforce recommendations

The Policing Bureaucracy Taskforce (chaired by Sir David O’Dowd, former

Chief Inspector of Constabulary) was established in January 2002 as part of

the Government’s Police Reform programme to seek ways to increase the

presence of uniformed officers in the community by:

• removing the unnecessary burdens borne by front-line staff

• providing adequate support

• revising working practices to enable them to operate more effectively.

The Taskforce report

9

identified that the public wanted to see more uniformed

police officers in the community and that front-line officers want to dedicate

more of their time to dealing effectively with crime and anti-social conduct and

in bringing offenders to book. It also acknowledged that there was a general

desire for the police and criminal justice professionals to succeed in convicting

the guilty and, in particular, persistent offenders whose activities blight the lives

of whole communities.

ANPR deploy to gather

intelligence on moving criminality

into / within / from area

Add to analysis of

previous ANPR deployment

in area (if any)

Analysis of ‘hits’ to

profile movement of

criminality in vehicles

Intelligence T&CG Process Tactical response

T&CG identifies issue

as priority for rescuing

T&CG consider

intelligence outputs to

inform Tactical Response

‘Semi-speculative’ deployment of

ANPR and Intercept Team as part of a

tactical response (crime analysis only)

Fully intelligence-led deployment of

ANPR and Intercept Team as part of

tactical response (crime and vehicle

movements analysis)

Option 1 Option 2

Intelligence gathered during deployment fed back into system

Figure 2.1: How ANPR contributes to NIM

9

Policing Bureaucracy Taskforce Report, Home Office (17 September 2002)

29

In relation to ANPR, the Taskforce recognised that ANPR was an extremely

useful tool; however it could only be fully effective if sufficient intervention

resources, specifically intercept teams, are deployed to respond to a

significant proportion of alerts. It recognised that ANPR:

• increased police performance in crime detection

• lead to higher police visibility and citizen reassurance

• could be partly self-funding through cost recovery

• could reduce time spent on paperwork by increased use of FPNs over

preparing traditional court files for appropriate offences.

The report made a specific recommendation to develop the use of ANPR.

2.2.3 The Bichard inquiry

The independent inquiry arising from the Soham murders chaired by Sir

Michael Bichard investigated a number of issues, including the effectiveness

of the relevant intelligence-based record keeping and information sharing with

other agencies and between forces.

The inquiry report

10

made a specific recommendation that the Home Office

should lead the development of a national information technology system

for England and Wales to support police intelligence and that it should be

introduced as a matter of urgency. Government has accepted these findings

and recommendations in full.

In this context it is important to note that other than for the services provided

by PNC, police forces are having to operate with a series of local databases

in regard to vehicle intelligence which have to be copied and shared between

forces. This is a time consuming and ineffective way of operating and highlights

the need for a national data warehouse. This could hold all vehicle intelligence

to be read in real time by all ANPR users nationally. In turn, this data warehouse

would also hold ANPR reads and hits as a further source of vehicle intelligence,

providing great benefits to major crime and terrorism enquiries.

2.3 The ACPO road policing strategy

The national ACPO roads policing strategy

11

presents the use of ANPR

as a core activity for the police to detect and respond to criminal activity

on the roads:

10

The Bichard Inquiry Report, Sir Michael Bichard, House of Commons (June 2004)

11

Modern road policing – a manifesto for the future, ACPO (November 2002)

30

“The police have a duty to tackle criminality, in all its forms,

including contravention of road traffic law much of which is

aimed at poor driver behaviour. We intend to use the police

National Intelligence Model to focus enforcement activity in order

to detect, disrupt and challenge criminal use of the roads. To do

this we will make full use of modern technology, and in particular

Automatic Number Plate Recognition systems that have the

potential to revolutionise road policing.”

To support the development and use of ANPR, ACPO have drafted an ANPR

information, intelligence and technology strategy

12

. The vision is to roll-out

Laser 2 to all forces such that approximately 2,000 officers are delivering an

intercept capability. This sets out how the Police Service will use ANPR,

specifically to meet its strategic aim of denying criminals the use of the roads

through a national infrastructure of ANPR technology throughout England and

Wales. The intention is to back this up by a police intercept team in every

Basic Command Unit area.

This strategy identified that every force in England and Wales has ANPR

capability and back office facility and shortly this back office facility will enable

ANPR data to be transferred between all forces through the secure and

controlled environment of the Criminal Justice Extranet (CJX). However the

strategy highlighted that while all forces have ANPR equipment, they are using

systems from a variety of suppliers. To address this PSU and ACPO have

recently prepared and circulated a National ANPR Standards document that

details the minimum standards within which police ANPR systems should operate.

This strategy, however, represents the Police Service strategy, and does cover

ANPR across Government, which includes DVLA, Customs & Excise, the

Highways Agency, VOSA, and ports authorities.

12

ANPR information, intelligence and technology strategy, ACPO (June, 2004)

31

2.4 The link between vehicle documentation

offences and crime

In the UK there is a high-level of non-compliance with vehicle documentation

requirements, for example:

• There are over 1.76 million vehicles on the road that do not have a valid

vehicle excise licence (approximately 5.5% of all vehicles on the road).

This evasion costs the HM Treasury (HMT) over £190 million per annum.

13

• DVLA have no registered keeper information for approximately 1.9 million

vehicles on the road. Anecdotal evidence from traffic police suggests that

where registered keeper information exists, the actual keeper is likely to be

different to the registered keeper in at least 10% of cases.

• The Association of British Insurers (ABI) estimates that there are at least one

million persons driving regularly while uninsured, ie about 5% of all drivers.

Accidents involving uninsured motorists cost up to £500 million a year, which

ultimately adds approximately £30 a year to each motorist’s premium.

14

• While no statistics are collected, it is believed that around 10% of those

vehicles requiring an MOT do not have a current MOT certificate.

Following a nationwide police operation to assess the level of non-compliance

on the roads, the DfT is expected to publish more information on the above in

the autumn of 2004.

2.4.1 There is a correlation between vehicle and traffic offences

and other criminality

Historically, police have not focused on these offences for a number of

reasons. First, the offences themselves were not seen to be as important

as other volume crime. However, evidence suggests that there is a strong

correlation between vehicle crime and other, more serious, crimes – for

example a Home Office study

15

demonstrated the link between traffic offending

and general criminality. The study found that of those parking illegally in

disabled parking bays:

• 21% of vehicles were of immediate police interest

• 33% of keepers of the vehicles had a criminal record

• 49% of the vehicles had a history of traffic offending

• 18% of vehicles were known or suspected of use in a crime

• 11% of vehicles were in breach of traffic law, eg no VED.

13

Vehicle Excise Duty Evasion, Department for Transport (2002)

14

New Research on Uninsured Drivers, Association of British Insurers (March 2004)

13

Illegal Parking in Disabled Bays: A Means of Offender Targeting, Sylvia Chenery, Chris Henshaw

and Ken Pease, Home Office RDS (1999)

32

These figures are significantly higher than the ‘average’ vehicle/vehicle driver.

The Home Office has also completed a study of the criminal history of serious

traffic offenders

16

. The study examined the extent to which anti-social behaviour

on the road was linked to wider criminal activity. It looked specifically at drink

drivers, disqualified drivers and dangerous drivers. A finding was that disqualified

drivers showed a similar offending profile to mainstream criminal offenders.

79% had a criminal record (72% for mainstream offenders), their levels of

previous offending were slightly higher than for mainstream offenders and they

were equally likely to be convicted again within a year (37% were reconvicted).

Importantly, however, police used prior intelligence in only half of all arrests.

This suggested that if police were able to access previous convictions in a

timely fashion, this could help more effectively target resources.

An important point that emerged from the study was the level of non-

specialisation of offence types – those repeatedly committing serious traffic

offences were also likely to commit mainstream offences. The evidence

suggests that these offenders cannot generally be thought of as otherwise

law-abiding members of the public. Even drink drivers (who were less involved

in mainstream crime than other serious traffic offenders) were estimated to be

twice as likely to have a criminal record as members of the general population.

When serious traffic offenders were reconvicted, there was a tendency for

repeat serious traffic offending (especially disqualified driving) although this

was in a context of more generalised criminal offending.

Recent research by the insurance industry evidences the strong link between

serious motoring offences and the one million motorists driving without

insurance

17

. Specifically, compared to drivers with insurance, uninsured

drivers are:

• ten times more likely to have been convicted of drink driving

• six times more likely to have been convicted of driving a non-roadworthy

vehicle

• three times more likely to have been convicted of driving without due care

and attention.

Finding 2. There is substantial research evidence to suggest that the

pursuit of vehicle documentation offences will lead to more serious

crimes being detected.

16

The Criminal History of Serious Traffic Offenders, Gerry Rose, Home Office RDS (2000)

17

New Research on Uninsured Drivers, Association of British Insurers (March 2004)

33

2.4.2 Scarce police resource is being stretched

A second reason why vehicle documentation enforcement has not been a

police focus has been the significant resource constraints upon traffic

police, ie those officers who would normally undertake vehicle documentation

enforcement. For example, a study published in 2003

18

estimated that less

than 6% of police personnel are dedicated to traffic and vehicle duties. In spite

of an increase in traffic volume (8% increase between 1997 and 2002)

19

and

vehicles (13% increase between 1997 and 2002)

20

, the number of designated

road traffic police fell by 13% between 1997/98 and 2002/03 to approximately

6,900 officers. An analysis of activity undertaken by these traffic police

officers

21

showed that less than 5% of their time was spent on static vehicle

checks and vehicle documentation checks – this equates to approximately

350 full time officers across England and Wales

22

.

Finding 3. These figures suggest that relatively little police time is spent

undertaking proactive vehicle checks and, given the above link between

vehicle documentation offences and more serious crime, this appears to

be an opportunity lost to address wider criminal issues.

Finally, police have not focused on vehicle documentation enforcement due

to the sheer volume of traffic on the road – in the UK there are nearly 30

million vehicles currently registered and over 485 billion vehicle kilometres

driven on the road network per year

23

.

Finding 4. The distances travelled on the UK roads presents a huge

logistical problem for police in terms of identifying and filtering out

vehicles worthy of stopping.

With the improvements in ANPR technologies and an overall reduction in IT

costs, it has been proven that ANPR can address these difficulties and become

an effective policing tool

24

. Criminals, like other citizens, need to use the roads

and, given the potential of ANPR allied with good police intelligence, when

they do so they are susceptible to detection.

18

Roles and responsibilities review Highways Agency/ACPO, PA Consulting Group (2003)

19

Road traffic: by type of vehicle: 1992-2002, DfT (2004)

20

Ibid

21

Roles and responsibilities review Highways Agency/ACPO, PA Consulting Group (2003)

22

While vehicle document checks may be undertaken by ordinary officers, no data exists on the

volume undertaken

23

Ibid

24

Engaging criminality – denying criminals use of the roads, PA Consulting Group (October 2003)

34

2.4.3 The public want more action taken against illegal drivers

In terms of public perceptions, surveys of motorists reveal strong support

for action against documentation offences. For example a recent survey

found that:

25

• three quarters of people surveyed are worried about the number of uninsured

drivers on the road

• more than nine out of ten (97%) people urged the Government to do more

to tackle this problem

• in terms of specific actions against uninsured drivers:

– a third of those questioned would like to see offenders taken off the road

for good with a total driving ban for culprits

– a third favoured confiscation of the vehicle

– a fifth would welcome larger fines

– while a fifth favoured imprisonment.

In terms of industry support, it is interesting to note that in their response to the

current Government review of the uninsured drivers, the ABI recommended:

26

“We need to see a step-change in enforcement processes, to

improve the actual and perceived chances of uninsured drivers

being caught. A new modern and cost-effective enforcement

process needs to be introduced. . .”

25

Commissioned by MORE TH>N and conducted by TNS via telephone interview amongst 1,006

GB adults aged 16+ from 11-13 June 2004

26

Response of The Association of British Insurers on behalf of Motor Conference and the MIB to

The Greenaway Review of Compulsory Motor Insurance and Uninsured Driving, ABI (February

2004)

35

Finding 5. There is significant public and industry support for a radical

change in the way documentation enforcement takes place, in particular

there is support for enforcement to target uninsured drivers. However, a

legislative change is needed to allow the proactive targeting of vehicles

without insurance (by using intelligence provided by an insurance

database). This would also help to increase the productivity of ANPR

intercept officers.

Finding 6. There is a major drive within policing to make better use of

intelligence, both as a means of targeting resources and to engage with

criminality. In the context of this report, it is clear that as an intelligence-

led policing tool, the effectiveness of ANPR in engaging level 2 and 3

criminality will be limited by the availability of good quality and timely

intelligence.

36

This section of the evaluation provides more information on how ANPR

intercept teams function. In terms of operation, the use of ANPR intercept

teams represents a radical approach:

• targeting vehicle documentation enforcement to engage with and

disrupt criminals

• delivering through an intelligence-led piece of technology

(an ANPR reader)

• benefiting from officers’ experience (eg observations of vehicle drivers)

• supported by existing policing processes (eg prisoner handling)

[Section 3.1].

ANPR monitoring can be undertaken by a number of means, principally

through fixed infrastructure (CCTV systems), within existing patrol cars

(in-car systems) or as a dedicated mobile unit. No one method of

deployment is significantly more accurate in terms of VRM reads – the

key issue is how the police operate the systems to meet local operational

targets. It is worth noting that ANPR-enabled intercept teams do not rely

solely on ANPR technologies but also use their training, experience and

judgement. Vehicles that are not flagged by the ANPR system but are

being driven suspiciously can also be stopped [Section 3.2].

How Laser 2 APNR

intercept teams operate

37

In terms of data sources, ANPR can be used with any database that

includes reference to a VRM. Within Laser 2, the principal data sources

were Police National Computer (PNC), local force information systems

and DVLA’s databases of vehicles recorded as not having VED or a

known keeper.

Programmed improvements to existing vehicle databases (DVLA and PNC)

and the development of legislative powers to use other databases proactively

(eg motor insurance database) will provide more and better quality

intelligence to ANPR intercept teams. With the success of ANPR intercept

teams, non-ANPR intercept officers are beginning to supply more vehicle-

based intelligence for the ANPR teams to exploit. Most national vehicle

databases are or will shortly be available for ANPR intercept teams.

While there is still a need to provide this intelligence as part of a national

data warehouse, these will allow ANPR teams to be more effective,

particularly in stopping those vehicles that appear on a number of

databases (‘multiple hits’) [Section 3.4].

3.1 Introduction

ANPR systems read VRMs from digital images, captured either through in-car

systems, closed circuit television camera (CCTV), or a mobile unit (normally

mounted in a vehicle). A key feature of all ANPR systems is their speed and

efficiency of analysis – the systems are capable of checking up to 3,000

number plates per hour of vehicles travelling up to 100 mph. Individual ANPR

units can link up to four cameras and cover several lanes/locations at a time.

Older systems were susceptible to crude manipulation of number plates

(for example using black insulation tape to change an ‘F’ into an ‘E’), and

functioned badly in poor visibility conditions. Newer infrared cameras combine

the latest software, are much more reliable and are able to accurately read

most VRMs – in practice this means ANPR systems are able to correctly

read 95 number plates out of 100.

The conversion of an image of a registration plate into text allows this data

to be used in a variety of ways including cross-referencing with databases.

This process is performed in a fraction of a second. Within a policing context,

ANPR can be used to identify vehicles flagged on the Police National

Computer (PNC), local Force Intelligence Systems (FIS) or other related

databases (eg DVLA or Customs and Excise).

38

Where there are support resources, action can then be taken immediately

– police know where a vehicle is and the direction in which it is travelling.

Prior to the introduction of ANPR, the volume of traffic helped to conceal those

committing vehicle-related crimes. The use of ANPR and dedicated intercept

teams can thus allow police to actively engage with criminality.

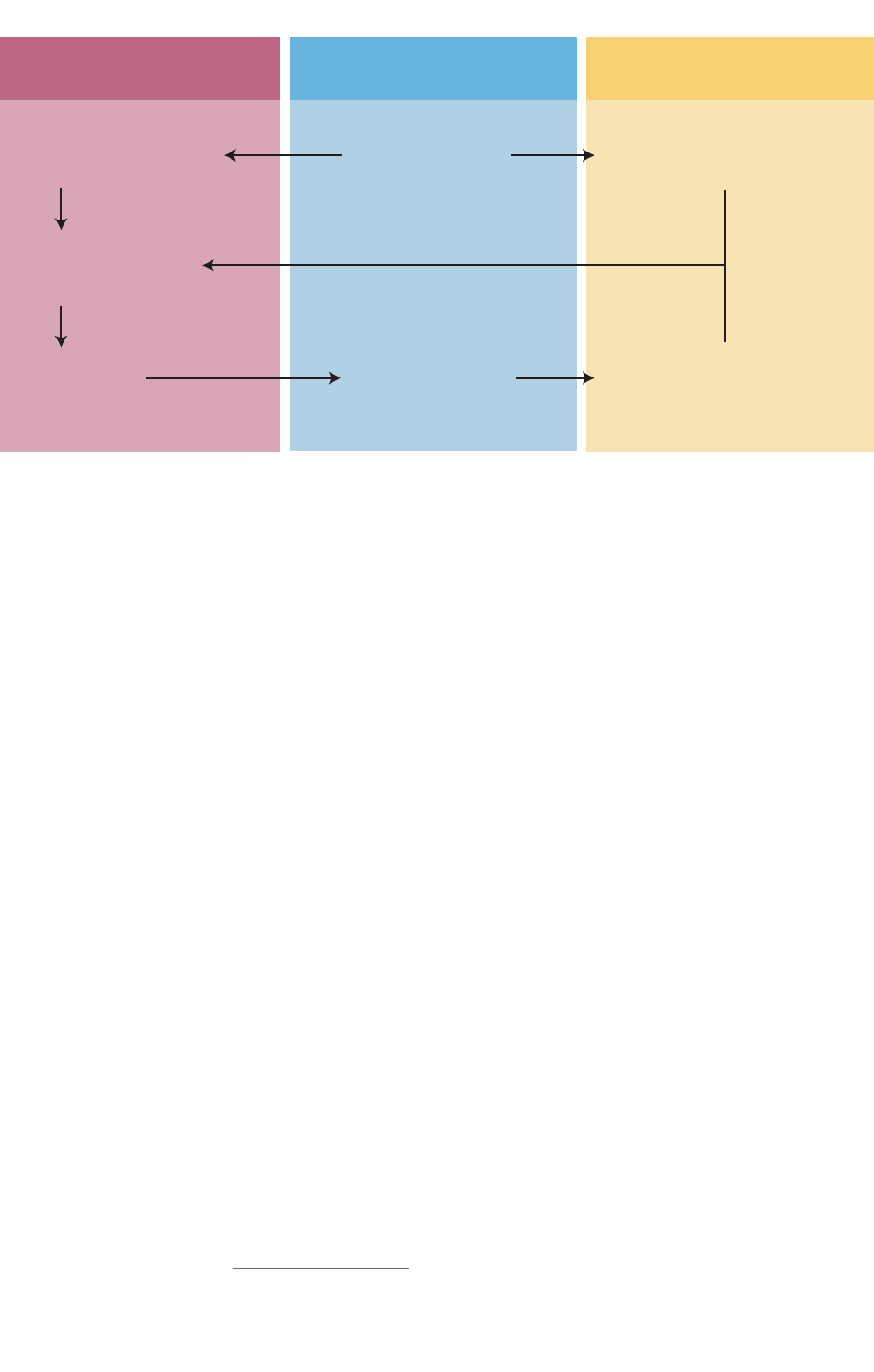

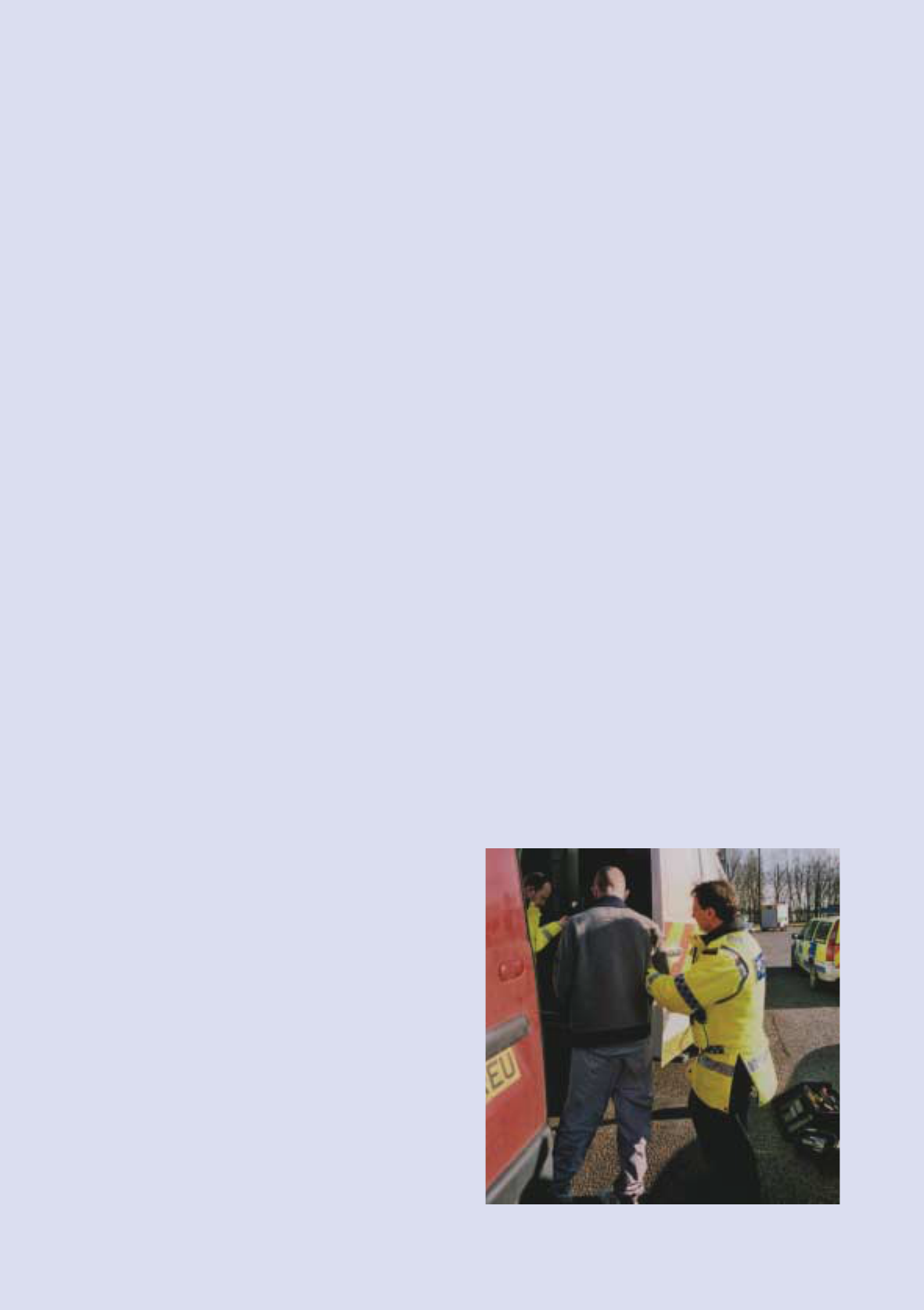

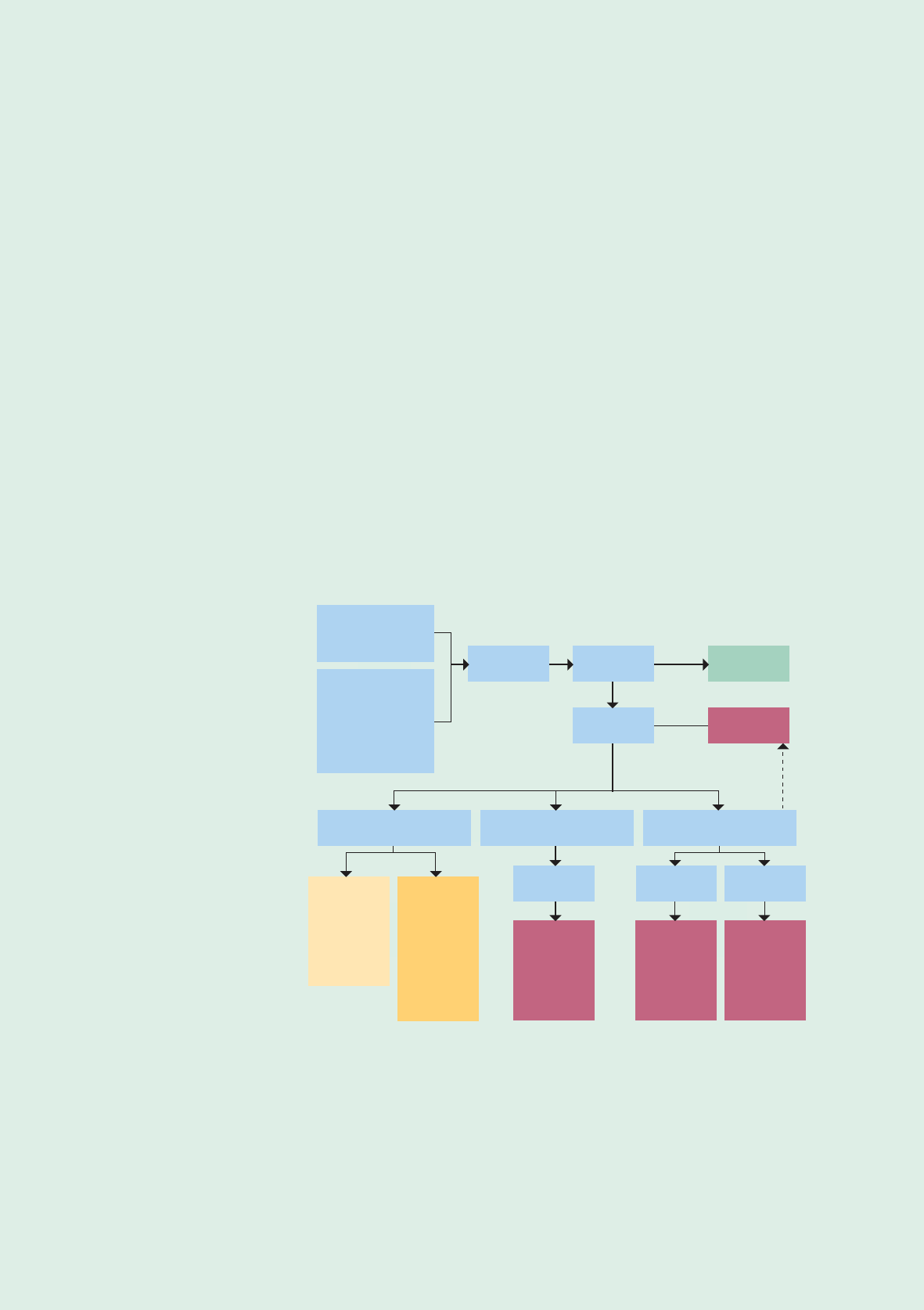

An example of how ANPR can be used with intercept teams is shown in

Figure 3.1. The vehicle passes an ANPR camera (either in-car, CCTV or a

mobile unit). This sends image data to the ANPR system, which ‘reads’ the

VRM and crosschecks it against a database; in this case the PNC and a

Force Intelligence System. Where a match is found, the ANPR operator is

notified and can decide to call for an intercept vehicle.

Figure 3.1: Use of ANPR to direct intercept teams

Stage 1

Vehicle passes

ANPR camera